The European Commission presented this month its action plan to become the global leader in artificial intelligence. But the bright future of EU competitiveness has some challenges along the way, with lawmakers, technology companies, and civil society groups already raising red flags. Several stakeholders even say the existing legal structures supporting the plan may create an “unfair scenario” among member states, and fear future discrimination of European citizens.

According to the project, named “AI Continent Plan”—the bloc will set its AI development on five pillars: building a large-scale AI infrastructure, increasing access to high-quality data, promoting AI in strategic sectors, reinforcing skills, and simplifying the implementation of the AI act.

To boost this development, the President of the Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, had already announced in February an investment of €200bn through the AI Invest initiative, with 10 per cent of that amount allocated to finance up to five AI gigafactories.

AI gigafactories on the way

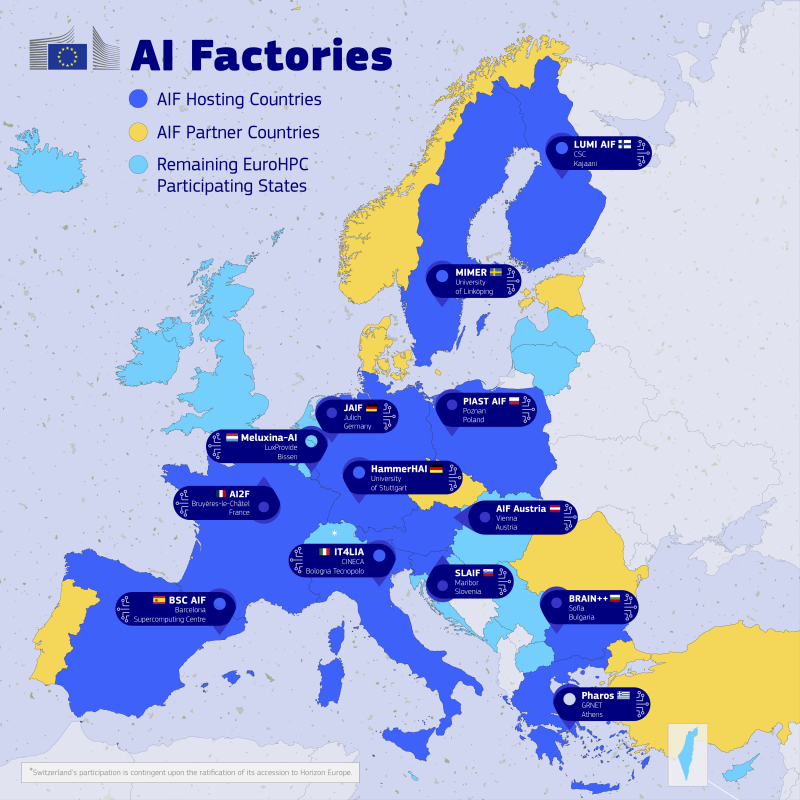

By the end of 2026, Brussels expects at least 13 AI factories and multiple antennas (linked to AI-optimised supercomputers in existing AI factories) to be operation-ready. The project will be hosted and developed by a total of 17 member states joined by two non-EU countries, under the European High Performance Computing Joint Undertaking (EuroHPC) initiative.

The bloc will mobilise an investment of €20bn through public-private partnerships to build up to five AI gigafactories in France, Spain, Italy, and Germany (the latter planning on having two of them). These large-scale facilities with gigantic computer power and data centres will allow the training of complex AI models at a scale never seen before.

Single market of data in a sea of uncertainties

One of the main goals of this training would be to break down language barriers among member states and create a single market of data. In an ideal world, this would mean a potential boost of intra-EU trade by up to €360bn.

But the path to the promising future envisioned by Brussels may not be so smooth.

You might be interested

For instance, training a complex AI model requires the collection of a vast amount of data – texts, images and sounds – from sources such as newspapers, books, songs, social media, or open archives. In order to do so, big tech companies demand more access to content online. And in fact, the Commission has already opened that door: its AI Act exempts text and data mining from the requirement that such companies comply with the 2019 copyright law.

“Europe is facing a choice that will impact the region for decades. It can harmonize regulation to foster innovation or risk becoming a technological backwater,” stated several Big Tech CEOs including Meta, SAP, and Spotify, in an open letter criticising the EU AI Act.

Although technology giants state the EU should facilitate even more access to content, and face fines of €35mn, or 7 per cent of global annual turnover if they fail to comply with the AI Act, creative industries across the EU have been vocal on the risks AI may present to the authorship of their production and intellectual property rights.

Several MEPs, including the rapporteur in the European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs (JURI), Axel Voss (EPP/GE), have been on the side of the creative industries, claiming there is “a legal gap” in the current law.

Henna Virkkunen, the EU Vice-President for tech, has admitted she is “aware of the criticism” but noted that the EU executive arm would “continue the work on these guidelines to industries, SMEs and AI developers”. The challenge, she added, remains in finding “the right balance” between “having European content to train and develop AI” and “respect copyright owners”, getting them “fair compensation when their work is used”.

Consumers and business safeties raise worries

In the global leadership race, Brussels sees artificial intelligence as a way to boost competitiveness. Yet, according to the Commission, only 13 per cent of EU companies currently use AI. Compare it to India, the global leader with 59 per cent of its companies using AI, as per last year’s study by IBM.

Success, however, may come at a cost, especially without a clear and comprehensive legal framework. Some MEPs were hoping the AI Liability Directive would address the issue by regulating artificial intelligence and establishing who is liable for harm caused by AI systems.

However, Ms Virkkunen announced the withdrawal of the directive in February, stating there was “no foreseeable agreement” to implement it. Before a new legal framework saw the light of the day, the Commissioner said, the executive would work on simplifying the existing one.

“Artificial intelligence is at the heart of making Europe more competitive, secure and technological sovereign. The global race for AI is far from over. Time to act is now”. — Henna Virkkunen, Executive Vice-President of the EU Commission for Tech Sovereignty, Security and Democracy

In response to the Commission’s decision, civil society and consumer groups sent an open letter to the tech Commissioner, and the Commissioner for consumer protection, Michael McGarth, urging the EU to work on new liability rules after the withdrawal of the AI Liability Directive.

The signatories – which includes BEUC, The Center for Democracy & Technology, and Mozilla – alert the Commission that “certain national regimes might adequately protect consumers and individuals affected by AI, but not all do”, and that without proper laws “it is very difficult, if not impossible, for the large majority of people to prove that it was the faulty behaviour of the AI operator that led to a certain harm”.

The issue left lawmakers divided.

When questioned by EU Perspectives about what should be next step for the Commission to take, MEP Sergey Lagodinsky (Greens-EFA/GE) said that it “should reevaluate the decision and continue working on the AILD”, since, from his point of view, the current legislation does not establish who assumes liability in the event of consumer harm originated by AI.

“Who is responsible when risks inevitably materialize? Those who develop, deploy, sell, or design? Or should responsibility be shared, and if so, how so? Neither the AI Act, nor the PLD, nor most of the 27 legal liability frameworks answer these questions,” he claims adding that “the Commission’s decision contradicts its own promises of simplification. Instead of reducing red tape, it increases fragmentation and legal unpredictability across the EU”.

The Commission’s decision left a climate of uncertainty, Mr Voss also claims. And uncertainty, he states, is not good for business. “Our citizens and companies will only develop and deploy AI if it is clear who will pay if something is going wrong. There will not be an AI ecosystem of trust within the EU, without EU AI liability rules,” he said.

On the other hand, MEP Svenja Hahn (Renew/GE), who backed the Commission’s withdrawal, argues that “the funeral of the new directive is positive for AI development and application in Europe”. The liberal member believes “AI liability is already sufficiently regulated in European and national laws” and therefore “the AI Liability Directive, along with the AI Act and numerous other laws, would have been an unnecessary and disproportionate burden for AI made in Europe”.

US threatens AI chips supply

Each future gigafactory will be set up with 100.000 state-of-the-art chips, which is “four times more than current AI factories”, the Commission says. The revolutionary modernisation may, however, be at risk as the internal market currently has no way to meet the demand.

AI chips are mostly designed in the United States and manufactured in Asia, which leaves the EU—with its reliance on imported US chips—and its strategic development goals in a vulnerable position.

Currently, the EU does not manufacture top-notch AI chips. To address this, the EU Chips Act aims to double chip production by 2030. But, as Commissioner Virkkunen admitted when quizzed by the European Parliament about the matter, “we are not there yet”.