Two years after the seismic Qatargate scandal, the European Parliament has continued to roll out stricter lobbying rules to curb covert influence. The Commission, too, has imposed more stringent guidelines. But the underlying political dispute—and the point-scoring—are as alive and well as ever.

From 1 May, lobbyists entering the European Parliament premises in Brussels must activate access badges at terminals, declaring the purpose of their visit—meetings with MEPs, staff, or attendance at events. The shift aims to “see who they meet and why they come into the Parliament,” said MEP and Quaestor Marc Angel (S&D/LUX), who oversees this administrative reform.

“Especially when it comes to interested representatives, be it from the business side or NGOs,” it’s important “that we can see who they meet and why they come into the Parliament,” Mr Angel was quoted as saying to reporters.

You want in? First, tell us why

The measures, agreed by Parliament leadership in March 2024, target a system where accredited lobbyists previously roamed freely with permanent badges. Now, each entry requires activation, logging details kept confidential by security—a move Mr Angel defends as necessary for “clarity and transparency” amid inquiries.

The reforms, some of which have already been in force for the last few months, follow December 2022 raids that saw suspects arrested, cash seized, and allegations that Qatar, Morocco, and Mauritania bribed EU figures for political favours. Qatargate, as the affair became known, thus exposed vulnerabilities: lax oversight of third-country influence and unchecked access for lobbyists bearing cash-filled suitcases.

You might be interested

Critics, however, argue that the rules sidestep deeper flaws. Lawmakers already face obligations to publicly register lobbyist meetings. But the new layer—part of a “wide-ranging reform package”—has irked advocacy groups. “The system adds bureaucracy without benefit,” fumed Emma Brown of the Society of European Affairs Professionals. “Lobbyists are already thoroughly registered—daily activation and visit disclosures are a needless burden. Transparency shouldn’t mean mistrusting everyone who walks through the door.”

As the Parliament fortifies its gates, the European Commission faces its own reckoning—of sorts. One of the figures implicated was Henrik Hololei, EU‘s ex-director general for transport from Estonia. In early May, he found himself at the centre of a disciplinary probe over alleged conflicts of interest, gift acceptance, and document disclosure.

Under the carpet

Internal documents seen by journalists reveal the inquiry follows a report by European Anti-Fraud Office, or OLAF, which found that Mr Hololei had shared confidential aviation-deal details with Qatar in exchange for luxury stays in Doha for himself and associates.

The case, first exposed by the French newspaper Libération, triggered an OLAF inquiry in 2023. In response, the Commission recommended disciplinary action, but said it found no “evidence of criminal conduct,” according to EC spokesman Stefan De Keersmaecker. Mr Hololei has accepted a demotion along with a pay cut—and that seemed to be the end of the story.

The European Public Prosecutor’s Office, or EPPO, disagreed. It opened a criminal probe in late 2024. The Commission offered no official response, but notified Mr Hololei on 21 March that he would face an internal disciplinary procedure; an official announcement to that effect came on 5 May.

The delay raised eyebrows as critics accused the Commission of foot-dragging. “The Commission was previously criticised for not taking measures,” noted the server Politico.eu after EPPO’s intervention.

A long-term conundrum

Mr Hololei’s case is attracting the spotlight at an inopportune time for the Commission. The Union’s executive arm finds itself sitting rather uncomfortably in the middle of a lobbying tug-of-war potentially more damaging than Mr Hololei’s penchant for luxury hotels.

In this case, the allegation goes that the Commission uses European money to finance NGOs through an opaque process in order to whip up more enthusiasm for its policies. The accusations are part of an old dispute recently pushed to the front burner by the growing radicalisation of Europe’s political scene.

It started in 2015 with MEP Markus Pieper (EPP/GE), not a great fan of NGO work. He was gathering support for his assertion that various Commission departments “exploit the distribution of EU grants for their own political agenda”. Since then, parliamentary conservative groups have pushed for more stringent oversight of how NGOs are financed, making the topic a hotbed of intra-EU institutional and political rivalries.

The controversy has generated extra attention because the process of NGO funding came under scrutiny of the European Court of Auditors. The Luxembourg-based institution’s action was, once again, motivated by the fallout from Qatargate.

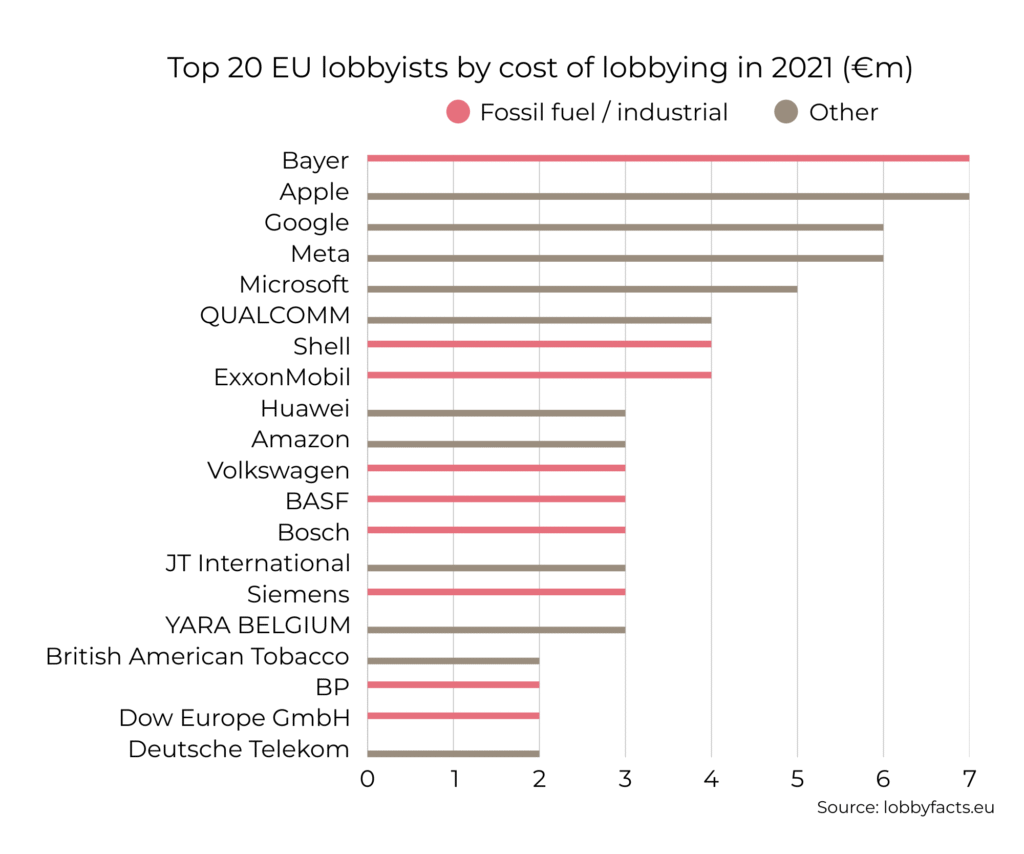

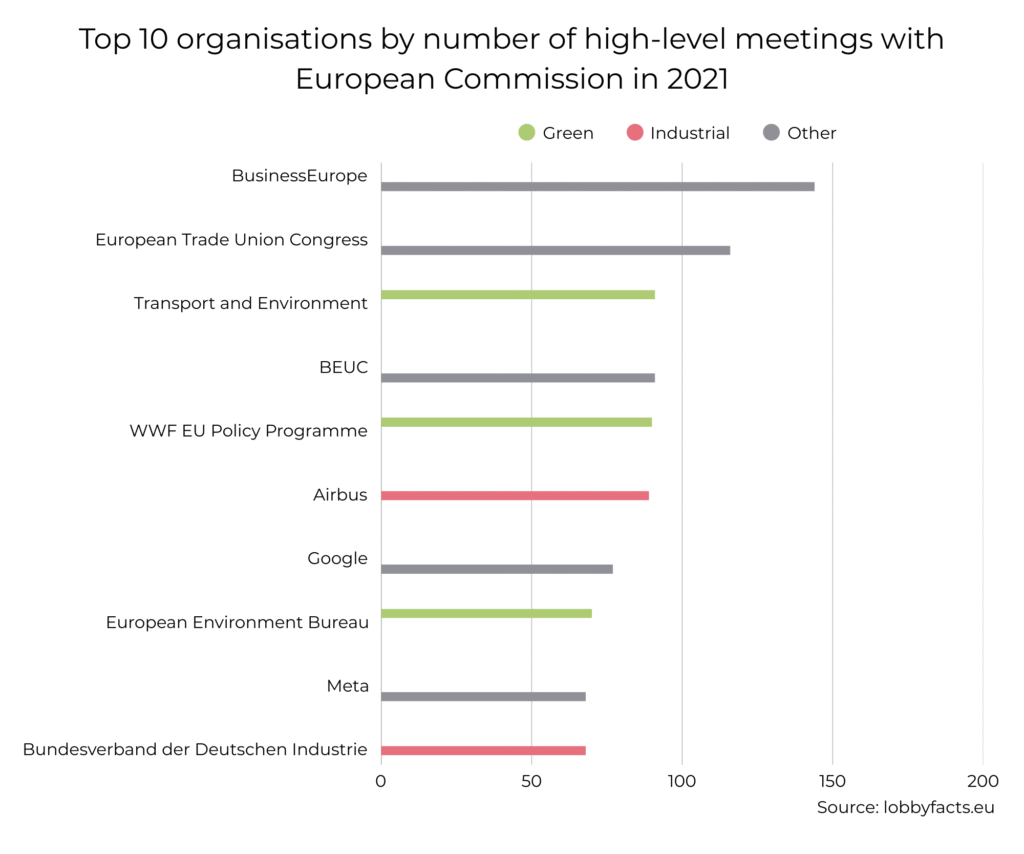

The basic outline of the conflict? Right-of-centre EP groups demand stricter rules for the financing of NGOs. Their left-of-centre opponents cry foul, asserting that tightening the screws is akin to silencing a vital participant of public debate, which gives unfair advantage to traditional industries with deep pockets.

Nonsense and disaster?

The core of the conservative argument is, however, just as political. Rather than the ostensible goal of ensuring a super-clean financing process, it appears that it is the environmental policies themselves what the conservatives worry about. This was highlighted last week during the European People’s Party congress in Valencia, where various speakers denounced the Green Deal, the Commission’s flagship environmental project.

Germany’s Bundeskanzler Friedrich Merz described some of the environmental rules as “nonsense”. Italy’s Antonio Tajani called it “a disaster”. “Europe must stop being a factory of new rules and start being a factory of growth,” said Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek prime minister.

The rightward shift of much of the EPP marks a departure from the established practice of Europe’s centrist parties sticking together to fend off attacks by fringe groupings on either side of the aisle. The left-of-centre groups, therefore, accuse the EPP of exploiting the issue in order to woo conservative/populist hardliners, both in the European Parliament and among the electorate.

On the ground, things came to a head in late March, when the Parliament’s ENVI committee came within a single vote of recommending MEPs to censure the Commission. The misdeed alleged by the proposed declaration (tabled jointly by the EPP and the ECR, to the dismay of liberal/left-leaning MEPs) was the Commission’s failure „to provide adequate safeguards to uphold the institutional balance in the Union by allowing the targeted lobbying of Members of the European Parliament on instruction of the Commission”.

Court of Auditors: No smoking gun

Oddly enough, the vote preceded the publication of a report by the European Court of Auditors on the matter. The Commission, the report reads, “has not adequately disclosed certain promotional activities (such as lobbying) funded by the EU, and checks are not actively carried out to ensure that funded NGOs respect the values of the Union, which is therefore exposed to a reputational risk”. However, the court did not find any smoking gun in the form of a clear breach of EU rules.

The matter is further complicated by the fact that the Commission did, in fact, adopt somewhat stricter funding guidelines as early as in May 2024. It did so in a characteristically oblique fashion: „In view of (the controversy), presenting specific positions to an EU institution or some of its members, including examining and explaining the impact of a given policy or policy proposal, should be entirely the choice of the entity concerned but not mandated as a requirement or condition for Union financing,“ the new guidelines read.

No lobbying!

In a comment issued in response to the narrowly averted parliamentary censure, the Commission explained that it „has recognised that in some cases work programmes submitted by the NGOs and annexed to the operating grant agreements contained specific advocacy actions and undue lobbying activities“.

In the intervening eleven months between the publication of the new guidelines and this past March near-censure, however, the Commission appears to have taken a more stringent approach. It told many recipients of its programme LIFE (which earmarks €5.4bn of funding between 2021 and 2027), including WWF, Friends of the Earth, and ClientEarth, that the money they receive from the EU can no longer be used for advocacy and lobbying work, Politico.eu wrote in late November. The NGOs received letters to that effect from CINEA, the EC agency entrusted with overseeing LIFE.

Troubled legacy

The NGOs in question were, quite predictably, less than happy. So were their sympathisers among MEPs. „Don’t Silence the Voices Fighting for Our Environment,“ read a typical headline on the website of We Move Europe, an environmental advocacy group. “Without civil society, public policy will end up being dominated solely by the interests of multinational corporations,” MEP Rasmus Nordqvist (Greens-EFA/DEN) said.

All of the aforementioned cases, loosely tied together as the troubled legacy of Qatargate, underscore Brussels’ struggle to police itself. The Parliament’s lobbying reforms ostensibly aim to deter future scandals but have an air of superficiality. Meanwhile, the Commission faces a complex landscape, balancing its policy goals with varying levels of public support. It is the politicians who keep scoring points.