After a fractious week of business meetings in Washington, the world grapples with uncertainty. For the European Union, an unforeseen window of opportunity opens. How much light it lets in hinges on how the bloc handles its internal divisions when facing the US amid a scramble for new alliances.

Global finance leaders departed Washington last week with little clarity on how to navigate US President Donald Trump’s (de)escalating tariff regime. The IMF’s downgraded growth forecast—2.7 per cent globally, 1.3 per cent for the US—pales against Bloomberg Economics’ dire projection: Trump’s tariffs could erase $2 trillion from global GDP by 2027. Karsten Junius, chief economist at Bank J Safra Sarasin, warned upon arrival to the meeting: “We have to find out how to do this without provoking Trump.”

The financiers have, by and large, managed to do just that, but at the cost of not having gained much in Washington. As the 90-day grace period for tariffs on around €380 billion of EU goods ticks toward a July expiry, Europe races to decode Mr Trump’s demands. But despite a flurry of meetings during the International Monetary Fund and World Bank Spring Meetings, European officials found themselves sidelined. Polish Finance Minister Andrzej Domański captured the mood: “We are not negotiating. We are just presenting, discussing the economy.”

He warned of the pervasive uncertainty harming both Europe and the US, adding, “They think it’s a short-term pain, long-term gain. And I’m afraid that we’ll have short-term pain, long-term pain.” The Trump administration’s focus remained on Asia, with “productive if inconclusive“ talks with Japan and South Korea.

Et maintenant?

What, then, is there to do, once the dust has settled somewhat after the tariff hurricane? The trade whiplash has frozen the economic outlook globally, but it may well offer Europe some silver lining. “A prolonged trade war between the U.S. and China could open up new sales markets for European companies,” Ludovic Suttor-Sorel, head of the European Macro Policy Network, a collection of think tanks, told Politico.eu.

„China already relies on European products in categories like chemicals and transport equipment, and that will likely grow. American demand for some European industrial goods that it previously bought from China—like machinery, plastics and textiles—could increase,“ Mr Suttor-Sorel said.

You might be interested

The European Union has, therefore, adopted a multi-pronged approach. It has tabled tangible proposals to stabilise trade relations with the US, though details remain scarce. Jozef Síkela, the bloc’s commissioner for international partnerships, struck an optimistic note: “We have to bring the stability back. Tariffs are a bad thing. For business, it is better to build bridges,” he added an insight.

Lots of ground to cover

However, while some negotiations are underway, the European Union has been also working on a proposal to introduce restrictions on some exports to the US as a possible retaliatory tactic. These would be used as a deterrent, should negotiations with the US — which has put new tariffs on around €380 billion of EU goods — fail to produce a satisfactory outcome, according to Bloomberg’s sources.

EU Economy Chief Valdis Dombrovskis acknowledged “lots of ground to cover” post-meeting with US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, even as he described their talks as “cordial and candid” to reporters in Washington. “We’re not going to hide the fact that we’re still a long way from an agreement,” French economy minister Eric Lombard told France24.com in the same vein. The outgoing German Finance Minister Joerg Kukies, though, said he was hopeful both sides could reach a deal before the 90-day window closed. “We’re optimistic that it will work, the sooner, the better,” he told the same media outlet.

The disparate responses underscore a recurring theme: Europe’s struggle to present a unified front. Until member states reconcile conflicting priorities, the Union’s negotiating position will be weak. That, in turn, would strengthen the hand of the US administration.

Asian pivot

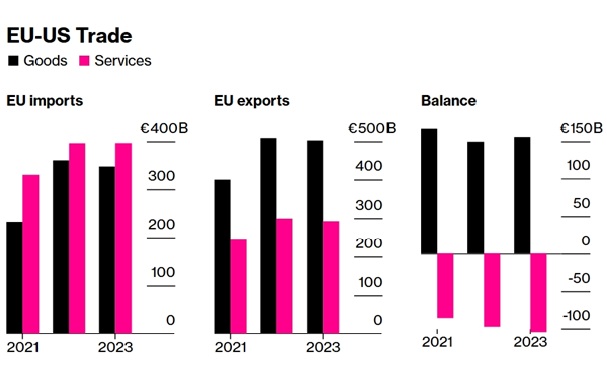

With transatlantic trade worth €1.6 trillion in 2023, diversification is as necessary as it is difficult. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen signalled openness to joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a 12-nation bloc excluding the US. “Europe continues to focus on diversifying its trade partnerships,” she said, highlighting EU‘s €2tn engagement with countries representing 87 per cent of global trade outside America. Recent talks with the UAE, Malaysia, and India underscore this pivot.

Ms Von der Leyen’s overtures to the CPTPP mark a strategic shift. The bloc, which includes Japan, Canada, and the UK, offers a lifeline amid strained US ties. Yet hurdles abound: Aligning EU standards with CPTPP rules on labour, environment, and state subsidies may easily either prove a roadblock to any progress, or force a European climbdown on some of the criteria, a trick Brussels doesn’t appear ready to do—yet.

European hopes of finding a way out of the trade maze have also seen a boost in the form of last week’s electoral triumph of Mark Carney’s Liberals in Canada. Mr Carney’s pragmatic liberalism brings Canada ideologically closer to Europe’s current leadership, the conventional wisdom goes. Trade remains the foundation of the Canada-EU relationship, based on the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, which has increased EU-Canada trade by 65 per cent since 2017.

Silver linings

Other potentially favourable developments have included China’s potential easing of sanctions on MEPs, seen as an effort to woo the EU amid the international uncertainty. While no resurrection is on the table of the dead and buried mutual investment deal intended in 2020, Beijing appears to be on a mission to sell itself as an attractive trade partner for the world.

Also, the UK and the EU have outlined a “new strategic partnership” aimed at bolstering trade (as well as presenting a united European front in the Russia-Ukraine war) in defiance of Mr Trump’s threats. A draft declaration being drawn up by London and Brussels ahead of a UK-EU summit on 19 May points to a “common understanding” on a number of shared interests.

The Trump administration can feel the mounting pressure. It responded to the nascent EU-UK deal the way it does best: with threats. “EU pact could scupper Britain’s hopes of free trade deal (with US),“ a headline by London’s arch-conservative The Telegraph read on Tuesday. But Rachel Reeves, Britain’s Chancellor of the Exchequer previously said the EU deal might be more important for her country than the US deal.

Uphill battles ahead

Yet the EU faces an uphill battle on most fronts. Secretary Bessent dismissed European readiness for talks, citing unresolved “internal matters” like digital service taxes in France and Italy. “It’s going to be a give-and-take,” he said, conveniently circumventing the fact that it is the US administration what is wreaking international havoc in the first place.

Bessent’s critique of Europe’s digital service taxes was aimed to expose fissures within the bloc. While France and Italy levy charges on US tech giants, Germany and Poland abstain. “We want to see that unfair tax on one of America’s great industries removed,” Mr Bessent reiterated what may emerge as a major sticking point in any future negotiations, in an apparent effort to highlight divisions among EU member states in order to weaken Brussels‘ position.

France’s stopgap

As Trump’s tariffs redirect cheap Chinese goods to Europe, France is spearheading countermeasures. Budget Minister Amelie de Montchalin proposed fixed handling fees on small packages from retailers like Temu and Shein by 2026. “It’s not a tax on consumers—it’s to make these platforms contribute more to checks we must do for security,” she said. Key points:

- fees ahead of a broader 2028 customs overhaul,

- the target is parcels under €150, currently exempt from EU levies,

- the point is to mitigate security risks and protect local industries.

This move reflects broader anxieties. With US tariffs on Chinese goods hitting 145 per cent, European policymakers fear becoming the next dumping ground for discounted apparel and electronics.

Uncertainty has seeped into corporate strategy. Louis Vuitton raised prices on its US bestselling Neverfull bag by 4.8 per cent post-tariffs. Michael Brown of Pepperstone, a UK broker, lamented, “Reacting to all these headlines is, frankly, a bit of a nightmare for both strategists and investors.”

“Before we slaughter them”

Markets yo-yoed as Trump dangled tariff relief for China, only for Mr Bessent to reaffirm their permanence. China’s Commerce Ministry rubbished claims of ongoing talks, with spokesman He Yadong calling such reports “groundless” even as various US officials insisted otherwise.

Meanwhile, the IMF struck a cautious tone, downgrading global growth forecasts but stopping short of predicting recessions. Privately, however, policymakers and hedge fund figures alike fretted to Financial Times and Bloomberg over higher recession risks than the IMF’s 37 per cent estimate, citing private-sector models.

What did catch a modest break however was the US car industry. Mr Trump’s Michigan visit heralded rebates for US-made vehicles and exemptions on steel/aluminium tariffs. “I’m giving them a little bit of a break,” he was quoted by Financial Times as saying. He went on to warn automakers worldwide: “We give them a little time before we slaughter them if they don’t do this right,” the man in the position once called the leader of the free world added with his trademark subtlety.

Adapt, adapt, adapt

With no deals struck in Washington and “reciprocal” 20 per cent tariffs looming, the bloc’s survival hinges on unity and agility. Whether through CPTPP outreach, digital tax compromises, or stopgap import fees, the EU’s multipronged strategy reflects a sobering reality: in Mr Trump’s trade war, adaptation is the only constant.