Lowering the existing Russian oil price cap down to 45 USD per barrel can severly harm the Russian economy and the same applies to EU’s efforts aiming at phasing out completely imports of Russian natural gas by 2027. Such a transition, however, may not be easy as in some EU countries it could bring economic troubles.

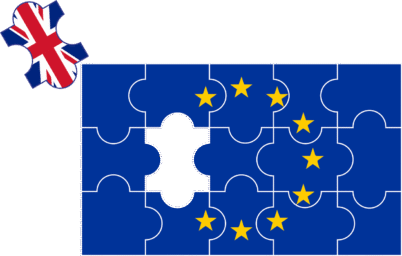

The European Union is preparing for its 18th sanctions package against Russia. This “hard-biting” set of additional measures is intended to “ramp up pressure” on Russia, according to Commission president Ursula von der Leyen. For the European People’s Party, sanctions are “the best leverage we have over Putin”. But the effects have so far proven more nuanced than that, and two years of economic warfare paint a complex picture of conflicting interests within Europe.

Despite the EU’s sweeping sets of sanctions, Russia’s economy has shown resilience. According to the International Monetary Fund, the country’s GDP grew by 3.6 % in both 2023 and 2024. Meanwhile, the EU’s growth marked just 0.6 % and 1.1 % in the same years.

You might be interested

Declining oil revenues

That does not mean that sanctions have not hurt the Russian economy. A recent report by the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA) and the Gaidar Institute warns that the country’s National Wealth Fund may dry up as early as next year. Accumulated from decades of significant oil and gas profits, the fund serves to cover budget deficits.

Sanctions are the best leverage we have over Putin. – Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission

But the fund has shrunk rapidly—from a peak of 113.5 billion USD in early 2022 to 36.4 billion USD today. The drop reflects both falling oil and gas revenues and the mounting cost of war. Approximately 21 billion USD is held in foreign currency, and 140 tons of gold remain – significantly down from 400 tons in 2022.

In its budget planning, Russia assumes an oil price of 70 USD per barrel. But current oil prices have been below 60 USD for three consecutive years. Should the oil price dive to 52 USD, the fund may be empty next year, the economists from the RANEPA warn.

As part of the latest sanctions package, the EU is now proposing to lower the existing G7 Russian oil price cap from 60 USD to 45 USD per barrel, a move that could further squeeze Russia’s budget and strain the Kremlin’s war treasury.

Phasing out Russian gas

Parallel to its efforts to strain Russia’s economy, Europe has also continued to fund Moscow’s war chest. In 2024 alone, EU gas imports from Russia totalled 23 billion USD – more than the bloc’s military aid to Ukraine.

For this reason, the European Commission announced last month that it wants the EU to completely phase out imports of Russian gas by 2027. Although the EU has long expressed this intention, it has so far proceeded cautiously: cutting gas imports drives up energy prices and weakens purchasing power for European citizens.

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen stressed that phasing out Russian gas is something the EU “owes to our citizens, our businesses, and our brave Ukrainian friends”, and urged member states to prepare national action plans by the end of the year.

During the transition period, no new contracts may be signed with Russian gas suppliers. Existing short-term contracts based on daily spot prices will be terminated by the end of 2025, cutting current flows by a third.

Difficult transition

But such a transition is not easily realised. France and Belgium, the EU’s two largest buyers of Russian liquified natural gas (LNG), have therefore not yet endorsed Brussels’ plan to ban Russian gas completely. The countries say they need more reassurances on the economic and legal consequences of the move before making a decision. Paris also warned of potential legal backlashes, as many privately owned European companies remain bound by contracts with Russian suppliers. France’s TotalEnergies, for example, holds a supply contract with Russian Novatek until 2032.

In the process of reducing its dependence on Russian gas, the EU has also turned increasingly to American LNG – a shift sparking fresh debate amidst the transatlantic political fallout. Danish Commissioner Dan Jørgensen who is responsible for energy and housing dismissed these concerns, stating he would “struggle to find any supply in the world that is as bad as Russia.”

Alternative suppliers are not without controversies

While there is a quiet acknowledgment that alternative suppliers also present their own moral dilemmas for the EU, the priority remains to sever direct dependency on the Kremlin, even if this requires compromises.

One of those cases is Azerbaijan. This week, Germany’s state-owned gas importer SEFE signed a 10-year deal with Azerbaijan’s SOCAR for up to 1.5 billion m³ of Caspian gas annually. Likewise, Commission President Ursula von der Leyen signed a landmark agreement with Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev in 2022, designed to double the bloc’s imports from the Asian country by 2027.

MEP Michael Bloss (Greens/GER) sharply denounced the deal his country made with Azebaijan: “It’s a scandal that German state-owned companies are shopping in Baku and financing Putin’s war chest! Putin’s gas is being relabeled and used to finance the war of aggression against Ukraine”, he stated on X.

Bloss’s remarks echo wider critiques that the EU may still be indirectly financing Russia’s war economy by ramping up imports from Azerbaijan. While the Commission has insisted this is not creating a back door for Russian gas to reach the continent, some studies suggest otherwise. A recent Global Witness analysis of Kpler trade data revealed a dramatic rise in EU imports of Russian-origin fuels from an Azerbaijani-owned refinery in 2024. A Chatham House article echoed the concern, warning that “Russian gas is being laundered through Azerbaijan and Turkey to meet continued high European demands.”

Fertilizers are “gas imports in another form”

As if phasing out Russian gas wasn’t complex enough, fertilizers present another thorny challenge for EU policymakers.

Russia remains a dominant player in the global fertilizer market, and its exports to Europe have rebounded rather than declined. In fact, the country’s share of EU fertilizer imports grew from 17% in 2022 to nearly 30% in 2024 — totalling over €1.75 billion. Globally, Russia exported $15.3 billion worth of fertilizers last year, with the EU accounting for around 13% of that sum.

In response, the European Parliament recently approved new tariffs on Russian fertilizers, starting at 6.5 % and set to rise to 50 % by 2028. However, critics argue this timeline is far too slow given the urgency of the situation. Ľubica Karvašová, Renew Europe’s shadow rapporteur on the file, emphasized the stakes: “As Europe moves decisively away from Russian fossil fuels, time has come to do the same with fertilizers — which are just gas imports in another form. This is a matter of food and economic security.”

Svein Tore Holsether, CEO of fertiliser manufacturer Yara International, echoed this concern: “Fertilizer is the new gas. Today, Europe and the world are more food dependent on Russia than before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The EU Commission wants to decrease Russian gas imports but, in a twist of geopolitical irony, we have ramped up imports of Russian fertilizers, which are heavily dependent on natural gas, and are now importing them at record levels. That is a paradox. And it is a vulnerability.”

Reducing dependency at the expense of farmers?

Farmers are apprehensive that rising tariffs on Russian fertilizers could push prices sharply higher, threatening their livelihoods. They feel sidelined by policymakers, who in their view, underestimate how severely agricultural producers will bear the costs of these sanctions. Dominique Dejonckheere, senior policy advisor at the farmers’ organization Copa-Cogeca, underscored this practical reality: Russian fertilizers remain the most competitively priced and reliably supplied option for many European farmers.

French MEP Marie-Pierre Vedrenne (Renew Europe) captured the difficult balancing act: “Every euro spent on Russian fertilizers indirectly funds Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. But we must not reduce this dependency at the expense of our farmers”.