Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen has kicked off her country’s six-month presidency of the EU Council with a clear, pragmatic message. Harden borders, speed up deportations, and rethink asylum, she says.

“People are coming from outside who commit serious crimes and do not respect our values and way of life,” Ms Frederiksen told MEPs in Strasbourg on Tuesday. “I don’t think there is a place for them in Europe, and they should be expelled.”

Her blunt language—delivered with European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen sitting just meters away—underscored the sharp pivot Denmark is making as it inherits the presidency from Poland. Migration and security will top the agenda in Brussels for the next six months, and Copenhagen intends to set the tone.

Right to feel safe

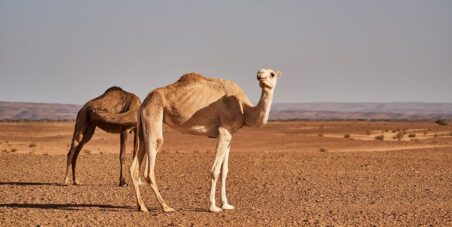

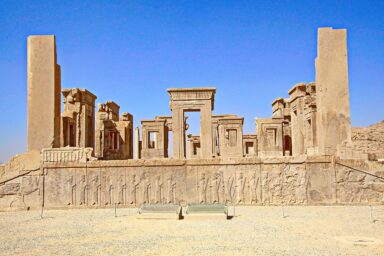

Ms Frederiksen called for new measures to curb irregular migration, backing Commission proposals to expand return procedures. She also supports building “return hubs” in third countries which sign such agreements with the EU. “This is an important step in the right direction,” she said. “We must strengthen our external borders,” she continued. “Our citizens have the right to feel safe. We must reduce migration flows, stabilize neighboring regions, and make return processes faster and more efficient.”

Denmark’s PM didn’t stop there. She acknowledged that the current EU asylum system is ineffective, warning that “cynical traffickers now decide who enters Europe.”

You might be interested

The remarks met swift praise from the right. MEP Nicola Procaccini (ER/ITA), co-chair of his faction and a member of Fratelli d’Italia, called the speech “refreshing.” “We conservatives have waited a long time to hear these words from a socialist leader,” he said.

Socialists divided

The Strasbourg plenary session thus witnessed a leader from Europe’s center-left deliver one of the EU’s toughest migration messages. In Ms Frederiksen’s view, migration control is not a betrayal of social democracy—but a prerequisite for its survival. “Who gets to enter and stay in our countries must be a democratic decision,” she said.

People are coming from outside who commit serious crimes and do not respect our values and way of life. I don’t think there is a place for them in Europe, and they should be expelled. – Mette Frederiksen, Danish PM

Within the Socialist & Democrats (S&D) group, reactions were measured. MEP Marina Kaljurand (S&D/EST), vice-chair of the European Parliament’s civil liberties (LIBE) committee, acknowledged divisions. Nevertheless, she stressed to EU Perspectives a common ground: “We agree on the need for a common migration policy, and the Migration Pact was a positive step.”

Ms Kaljurand admitted there are “different views on borders and the instrumentalisation of migration, especially between countries bordering Russia and Belarus and those further west,” but remained confident in the possibility of a balanced deal.

More third-country agreements

Ms Frederiksen’s sharp tone is not entirely new. In 2024, Denmark—under her Social Democratic government—joined 15 other EU states in calling for partnerships with third countries on migration, citing models such as the EU-Turkey Statement, the Tunisia Memorandum, and Italy’s controversial deal with Albania.

European Parliament President Roberta Metsola echoed Ms Frederiksen’s push. “We are working to move return legislation forward quickly,” she said, aiming to restore “credibility and sustainability” to the EU’s asylum system. “With the team we have, I believe we can deliver concrete results in the next six months.”