With the European Media Freedom Act set to apply from 8 August 2025, the EU is entering a critical phase. Based on the findings of the 2025 Media Pluralism Monitor, published by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Media Freedom, most member states are still facing challenges.

The European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) introduces legal safeguards against political interference, mandates transparency of ownership, and sets clearer rules for regulators and state advertising. The Media Pluralism Monitor, however, paints a picture of slow progress and uneven readiness across the Union.

While the EMFA is legally binding, the capacity to comply with and enforce it varies widely across the EU. From ownership transparency to editorial independence and fair advertising rules, the MPM 2025 highlights that many member states are still falling short. As Ms Brogi puts it, “…courts and regulators will be essential to making the EMFA work, but they need political support, legal clarity, and proper resources.”

Not all EU member states are ready — Elda Brogi, Deputy Director of the CMPF

“Not all EU member states are ready,” says Elda Brogi, Deputy Director of the Media Pluralism and Media Freedom (CMPF). “But the EMFA is a regulation; they will have to implement it regardless of their readiness. The full implementation will probably be a lengthy path, as it will require case law.”

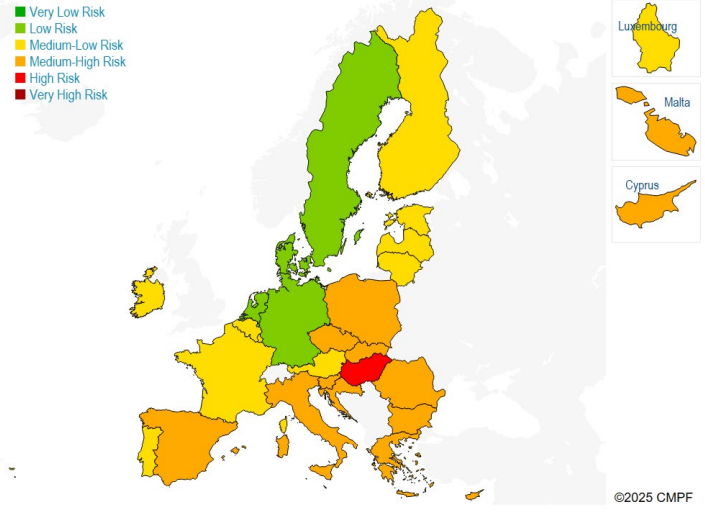

Uneven levels of media pluralism

According to the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM), only Germany, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands hit the low-risk mark when it comes to media pluralism. Most other countries, 22 in total, are in the medium-risk category, while Hungary has a high-risk rating, with a media environment described as “almost completely captured by the ruling political party Fidesz.”

The report highlights how political influence, ownership concentration, and regulatory weaknesses continue to undermine media independence in many countries. Ms Brogi points to persistent institutional resistance: “Some member states consider it a matter of national sovereignty. Hungary, for instance, has contested the EMFA’s legal basis before the Court of Justice.”

Hungary, for instance, has contested the EMFA’s legal basis before the Court of Justice — Elda Brogi, Deputy Director of the CMPF

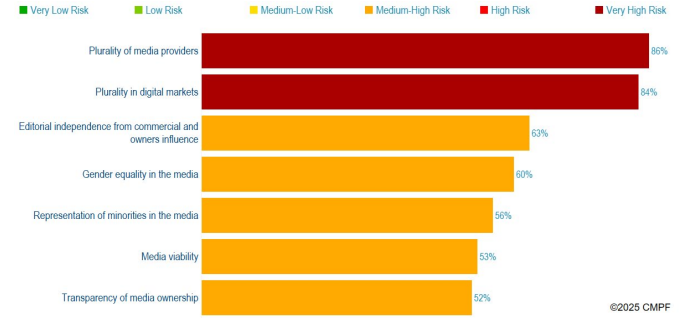

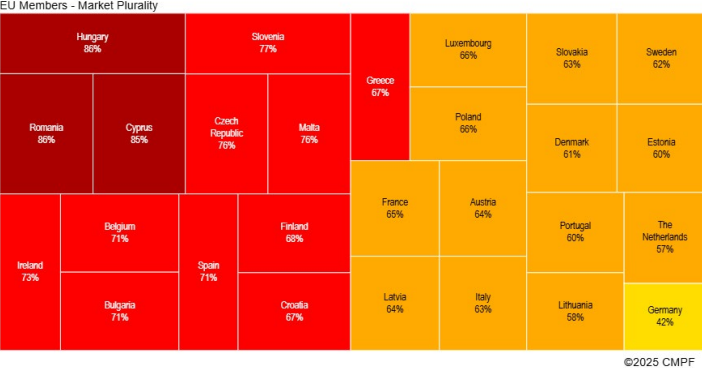

Market concentration as a major concern

The MPM identifies media market concentration as one of the weakest areas. No country scores low risk. Cyprus, Hungary, and Romania stand out as very high-risk due to extreme ownership concentration and the absence of specific merger controls for the media sector.

Despite Article 22 of the EMFA introducing a “media plurality test,” many countries have not yet developed the necessary legal framework to enforce it. Some, like Germany and Italy, have limited mechanisms. These often exclude online media or lack criteria related to editorial independence.

There are signs of progress. For instance, the Netherlands’ antitrust authority referenced media plurality in its review of the DPG-RTL merger, which analysts view as a significant precedent.

You might be interested

“EMFA is already inspiring the internal debate in (member states) and, in some cases, also NRAs decisions,” Ms Brogi notes. “See the case of the Dutch antitrust authority’s approval of the DPG-RTL merger, as it is interpreted as the first time media plurality has been used in its assessments (…) The analysis in this decision closely mirrors the forthcoming media plurality test under the new European Media Freedom Act.”

Who owns the media?

Transparency of media ownership, a key EMFA requirement under Article 6, remains limited. The MPM finds that in many member states, it’s still difficult to identify the ultimate or beneficial owners of media outlets. Cyprus, Hungary, and Spain rank very high-risk on this measure.

Many countries still lack media-specific registries or cross-sectoral systems that include digital and online publishers. According to the MPM, progress towards national media ownership databases is desirable, but implementation is still at an early stage in most cases.

Political interference

The EMFA’s Article 7 calls for national regulators to be independent and adequately resourced, but the MPM shows that this is far from the norm. Hungary’s National Media and Infocommunications Authority (NMHH), which doubles as the country’s Digital Services Act coordinator, has a “heavy” political bend and tends to approve only pro-government mergers.

Even countries with stronger reputations, such as France and the Netherlands, do not enjoy quite plain sailing. Their regulators’ responsibilities have grown without a matching increase in resources.

Government surveillance and pressure on journalists, such as the use of spyware like Pegasus, compound concerns over editorial independence in some cases. This rings alarm bells about the broader erosion of media freedom across the EU.

“It is essential that National Regulatory Authorities are independent and well equipped in terms of budget and human resources to face the increasing number of tasks entrusted to them,” says Ms Brogi. “Sometimes not only by EMFA, but by the EU digital acquis at large.”

Media advertising still up for sale

The EMFA aims to make state advertising more transparent and fair, but the MPM finds that nearly every member state has problems in this area. Only Denmark, Austria, Portugal, and Spain score below medium risk.

In many countries, public advertising funds reward politically aligned outlets or influence editorial lines. The MPM warns that this distorts the media market and undermines trust.

EMFA is already inspiring the internal debate — Elda Brogi, Deputy Director of the CMPF

Public service media (PSM), expected under Article 5 to operate independently and offer balanced coverage, are also under pressure. The report mentions Malta, Hungary, Slovakia, Romania, Poland, Italy, Greece, and Croatia as high-risk countries. It describes their public broadcasters as doing their governments’ bidding, or lacking editorial independence.

Media freedom is a ‘priority of this Commission’

In response to questions about member state readiness, a Commission spokesperson emphasised the EU’s ongoing engagement: “Media freedom is a priority of this Commission, including the implementation of the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA). The Commission has been engaging with Member States to ensure that the implementation of the EMFA is on track.”

About what should happen next, Ms Brogi points to both institutional and political responsibility. “Courts are asked to interpret the act according to the highest standards on freedom of expression that have developed in Europe… [and] to disapply national laws that are in contrast with EU law.”

“I expect independent monitoring of the implementation from the EU and that Member States avoid interfering with the work of courts, NRAs, and media,” she says. “Reforms that abide [by] the highest standards of freedom of expression and media freedom and are informed by an open dialogue with a wide range of relevant stakeholders.”