Digital policies, from chip procurement to rules of online behaviour, are turning into the next transatlantic economic battleground. Europe’s tech producers complain the recent trade deal unjustly cements US dominance. American politicians and tech lobby, for their part, cry censorship over EU regulations.

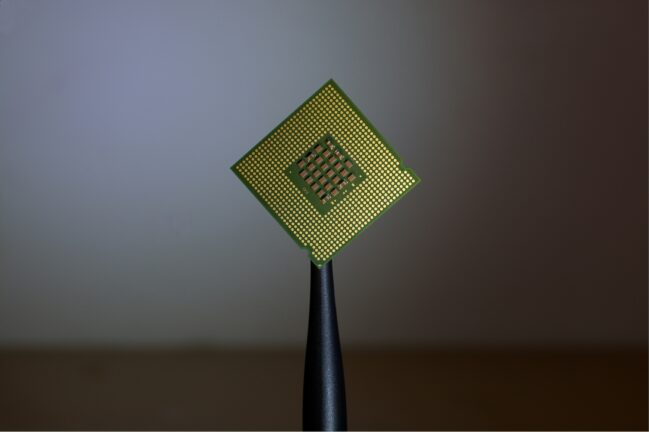

Last week’s EU–US trade agreement has reignited debate about Europe’s dependence on US digital technologies. The agreement, finalised on July 27, 2025, imposes a 15 per cent tariff across core sectors like automobiles, semiconductors, and pharmaceuticals. Artificial intelligence chips, which EU companies buy mostly from across the Atlantic, played an important role.

EC Commission President Ursula von der Leyen affirmed that EU companies would continue purchasing them from American suppliers. “US AI chips will help power our AI gigafactories and help the US maintain its technological edge,” she said.

Calls for digital sovereignty

Formally speaking, the chips do not enjoy the exemption status from the 15 per cent tariffs, included in the deal for some items. Aircraft, select chemicals and generic medicines, critical raw materials, and semiconductor manufacturing equipment do.

Ms von der Leyen’s public commitment to buy US-made AI chips aligns with existing EU procurement strategies. Still, it raises concerns among advocates of technological sovereignty, particularly in light of the EU Chips Act’s goal to reduce foreign dependency in critical technologies.

You might be interested

US tech giants remain untouched, despite their significantly more favourable tax treatment than many European firms. – Oliver Grün, President of European Digital SME Alliance

The European Digital SME Alliance, which represents over 45.000 small and medium-sized technology companies across Europe, has warned that the structure of the agreement thus tilts heavily in favour of US technology interests. In a statement, the Alliance noted that Europe already imports more than €300bn in digital services from the US annually.

Unfair advantage

“Commitments to increase imports of American LNG, AI chips, and military products will channel significant European investment into US industries at the expense of European capacity building,” said Oliver Grün, the Alliance president. He added that “US tech giants remain untouched, despite their significantly more favourable tax treatment than many European firms.”

The organisation has called on the Commission to use upcoming technical negotiations to introduce safeguards for digital sovereignty and to accelerate the development of a competitive European tech stack.

US AI chips will help power our AI gigafactories and help the US maintain its technological edge. – European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

Ms von der Leyen has so far only described the deal as a “clear ceiling” to provide predictability for European businesses, noting that it applies without stacking or sector-specific surcharges. The emphasis on the latter may find an explanation in the Commission’s effort to maintain the appearance of the entire trade deal staying within WTO rules.

Free speech under threat?

Meanwhile, the Americans opened fire on another front of the tech battle, EU digital rules. Just days before the agreement was finalised, the Computer & Communications Industry Association (CCIA) released a report estimating that EU digital regulations cost U.S. companies up to $97.6bn annually, including $32.9bn in lost revenue, $2.2 billion in compliance costs. Just meeting DMA obligations sets them back to the tune of $1bn per year, the association claims.

The lobbying effort was timed to underscore US concerns that European digital regulation has extraterritorial effects on American firms. This resonated with some US policymakers, particularly of the MAGA strand. Two days before the finalisation of the deal, US House Judiciary Committee head Jim Jordan, a fervent Trumpist, released a report condemning the EU’s Digital Services Act as a threat to free speech.

The report argues that the DSA forces American tech companies to enforce European content rules that would violate the First Amendment if applied in the U.S. “Taken together, the evidence is clear: the Digital Services Act requires the world’s largest social media platforms (many of which are American) to censor core political speech affecting users in Europe, the United States, and around the world,” Mr Jordan wrote in a post on a X post thread which he called “The EU Censorship Files”.

Foreign censorship fears

Citing specific cases, he pointed to a French regulator’s decision to order the removal of a satirical post about immigration policies in the wake of a violent attack by a Syrian asylum seeker. In Germany, authorities classified a call to deport immigrants with extensive criminal records as “incitement to hatred” and demanded the post be taken down.

Mr Jordan warned that such takedowns, once national in scope, may now apply globally. “European courts have empowered national regulators to issue global content removal orders,” he noted, adding that the DSA is “a foreign censorship regime that affects Americans’ right to free speech.”

The Judiciary Committee, under Mr Jordan’s leadership, has launched a broader investigation into what it calls “foreign threats to American free expression,” and is actively subpoenaing communications between platforms and EU regulators. “Big Tech continues to produce their communications with foreign government censors on an ongoing basis to the Committee under subpoena,” he wrote.

Digital power plays

This comes despite European officials insisting that regulation was not part of the tariff negotiations. “There is absolutely no commitment on digital regulation, nor on digital taxes,” a senior EU official told Politico.

The EU–US tariff deal offers short-term relief for Europe’s tech sector, particularly in semiconductor manufacturing. But the deeper challenge remains unresolved: reducing the EU’s dependence on U.S. platforms, suppliers, and digital infrastructure. It also made clear that digital regulation is no longer just a domestic policy issue; it has become a central front in the shifting balance of power between Brussels and Washington.