The European Union chose November 20th to unveil a fresh bargain with its southern neighbours. The Pact for the Mediterranean, drafted in October and now blessed by the Council, declares the region a strategic priority.

Officials trumpet the deal’s ambition. The Common Mediterranean Space, Brussels hopes, will reset relations, turn shared problems into shared projects and, above all, produce visible results. The approved conclusions speak of “enormous potential” and promise to “create bridges among people and countries that foster mutual understanding”. A new governance system will track progress each year, while the European Commission must translate lofty language into an action plan that everyone can grasp.

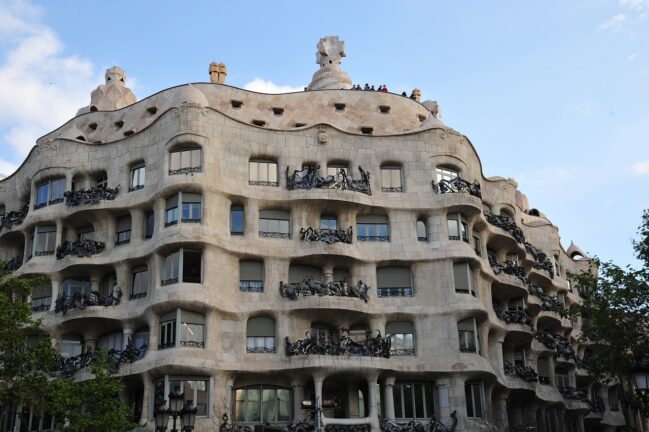

The pact draws strength from a three-decade history of co-operation. The Barcelona Declaration is the founding document of the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership, often called the Barcelona Process. Signed in the city of Barcelona on 27–28 November 1995, it brought together the 15 European Union members of the time and 12 countries from the southern and eastern Mediterranean (Algeria, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Malta, Morocco, the Palestinian Authority, Syria, Tunisia and Turkey).

One pact, three pillars

Since the 1990s, the tone has shifted. Past declarations felt abstract. This text brims with to-do lists and deadlines. That change reflects rising pressure over migration, climate and growth. Vague pledges will no longer satisfy restless voters on either shore.

The agreement stands on three pillars, as EU projects are prone to doing. First come “people: driving force for change, connections and innovation”. The Union vows to boost schools, research links and youth jobs, and to protect cultural sites that still lure tourists. Second are “stronger, more sustainable and integrated economies”. The focus here is on trade corridors, the “blue economy” of ports and fisheries, and cleaner energy grids that stretch across the sea. The third pillar covers “security, preparedness, and migration management”, a blunt recognition that boats, borders and smugglers dominate headlines.

You might be interested

Human rights run through the text. EU capitals commit to “upholding and promoting human rights, good governance, democracy, the rule of law and fundamental freedoms”. They also promise a “whole-of-government, whole-of-route and rights-based approach” to migration. In plain speech that means cash and training for coastguards, better shelter for asylum-seekers and quicker returns for those denied protection.

Money talks

What does this look like on the ground? Expect modernised ports that shave hours off shipping times, solar farms in sun-scorched deserts feeding power northward and vocational schemes that steer restless graduates into skilled work at home rather than precarious jobs abroad.

Good intentions need money. Ministers urge “adequate financial resources” and want private investors to swell public funds. The pact ties into the EU’s Global Gateway plan, which seeks to mobilise billions for infrastructure. Critics note that earlier promises often stalled. Supporters counter that a single framework, backed by strict reporting, will concentrate minds.

The objectives set three decades ago—to bring peace, stability, sustainable, shared prosperity and competitiveness to the people of the Mediterranean—can be achieved. — the European Council in its Conclusions on the Pact for the Mediterranean

Security co-operation will test trust. The text calls for joint work on “conflict prevention, mediation, organised crime and maritime safety and security”. Some partners worry about sovereignty; others fear that aid will dry up if targets slip. Brussels insists that progress will unlock trade perks and green finance. Even sceptics may accept that bargain if it brings jobs and foreign currency.

Beyond slogans

Climate action could unite the sides. The Mediterranean suffers drought, fires and coastal erosion. The pact lists water scarcity and vows to enforce environmental rules agreed years ago under the Barcelona Convention. Cleaner ferries, efficient desalination plants and coastal defences should follow, though permits and procurement can move at a snail’s pace.

Communication matters. The Council stresses “robust outreach and strategic communication”. That should mean fewer acronyms and more proof. Ordinary citizens will judge the pact by things happening on the ground, not by press releases. One of the most acutely felt things happening on the ground is migration, the sharpest political issue. Legal routes for students and workers could ease pressure if member states set real quotas. Failure would fan populists who see every rescue ship as a threat. Success would show that managed migration can fill labour gaps while cutting the smugglers’ trade.

The Pact for the Mediterranean packs clarity and ambition into 12 pages. Turning those words into cranes, classrooms and clean energy will decide whether the “One Sea, one Pact, one Future” slogan (somewhat eerily resembling Adolf Hitler’s “ein Volk, ein Reich, ein Führer“ in its form) earns substance—or sinks like so many earlier schemes.