The European Union on Monday did not produce a substantive response to US President Donald Trump’s threats to forcibly annex Greenland. Its team of spokespersons dodged basic questions on the potentially vital security issue.

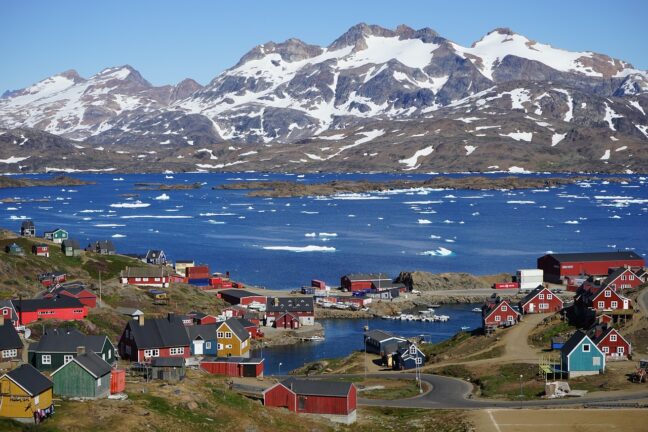

The European Union deals with an issue nobody thought possible even a year ago: How to avert a possible act of American aggression against a European NATO ally. This is because the US President, Donald Trump has devised just such a plan. Fresh from trumpeting the seizure of Nicolás Maduro, the American president told The Atlantic on Sunday, “We do need Greenland, absolutely. We need it for defence.” His deputy chief of staff’s wife plastered a stars-and-stripes meme over the island with the caption “Soon”. Copenhagen bristled, Nuuk fumed. Brussels reached for its talking points.

Inside the Berlaymont, Paula Pinho, European Commission spokeswoman, repeated a familiar pattern. “The EU will continue to uphold the principles of national sovereignty, territorial integrity, the unviolability of borders and the UN Charter. These are universal principles and we’ll not stop defending them,” she declared during a 5 January press briefing. Asked whether stronger language might deter Washington, Ms Pinho said only that Greenland lay within NATO and “we therefore completely stand by Greenland and in no ways do we see a possible comparison with what happened” in Venezuela.

Reporters pressed for concrete measures. Anitta Hipper, Commission foreign affairs spokeswoman, replied, “We expect all our partners to respect the sovereignty and territorial integrity and to abide by the international commitments. But there is nothing more at this stage we would go into.” When the questions turned sharper—was the US now an aggressor?—Ms Pinho shrugged. “We haven’t really discussed how we are calling it. I don’t think that’s the most relevant (issue) in the matter.”

You might be interested

Principles over power

The union’s treaties oblige member states to stand up for each other, yet Greenland, though part of the Danish realm, is not inside the EU. That fact offers some leeway.

Danish politicians want more than solidarity tweets. Mette Frederiksen, Denmark’s prime minister, called the American posture senseless and pleaded for an end to “threats against a historically close ally”. Jens-Frederik Nielsen, Greenland’s prime minister, bristled at being lumped with Caracas. “When the President of the United States says that ‘we need Greenland’ and links us to Venezuela and military intervention, it’s not just wrong. It’s disrespectful.” Yet neither leader heard a pledge of sanctions, military back-up or even an emergency summit from Brussels.

The EU needs us to have (Greenland) and they know that. — US President Donald Trump

The comparison to Venezuela rankles. Europe denounced Mr Maduro for years. But the Trump administration’s willingness to kidnap a head of state without United Nations blessing pokes a hole in Europe’s rules-based worldview. So far, the EU issued a statement that managed to urge restraint while hailing an “opportunity for a democratic transition”. That verbal contortion now haunts its dealings over Greenland.

Silence on the high north

Greenland matters far more to Europe than it might seem at first glance. Its minerals promise relief from Chinese supply chains; its air bases watch the GIUK gap, a maritime choke-point for Atlantic reinforcements. Yet Mr Trump told reporters aboard Air Force One that “the EU needs us to have it and they know that.” Invited to reject that claim during Monday’s press briefing, Ms Pinho demurred: “I’m not informed about any discussion with the US by our representatives on this issue.”

Such hedging infuriates Nordic diplomats. Norway’s envoy, off-record, frets that American bluster might spur Russia to mischief in Svalbard. Finnish officials whisper that Brussels’ airy rhetoric invites comparison with its dithering after Russia seized Crimea. For now, the European Council has not scheduled a single meeting devoted to Arctic security.

Threats without tools

Denmark, left to improvise, leans on bilateral ties. Copenhagen courts France for naval exercises and Germany for satellite coverage, while dispatching envoys to Washington in hope of lowering the temperature. EU aides insist this patchwork suffices because both Denmark and Greenland enjoy NATO’s umbrella. Yet Mr Trump has already shown disdain for the alliance’s niceties. In Caracas he acted first, consulted later.

I strongly urge the US stop the threats. — Mette Fredriksen, Denmark’s prime minister

Article 42.7 of the EU treaty obliges mutual aid to any member under armed attack, but offers Denmark no automatic guarantee for its overseas territory. The commission cannot propose sanctions against Washington without unanimous support, which Hungary would almost certainly veto. The European External Action Service lacks even a desk officer dedicated solely to Greenland.

Economics over geopolitics

Mr Trump’s Arctic obsession is not wholly whimsical. Climate change melts sea ice, shortening shipping lanes between Europe and Asia. Rare-earth deposits lie beneath Greenland’s tundra; uranium, zinc and nickel sparkle in prospectors’ reports. European new Critical Raw Materials Act names Greenland as a potential partner in reducing strategic dependence on China. If Washington claims exclusive rights, Europe’s supply-chain plans crumble.

Investors already smell trouble. Shares in Bluejay Mining, a London-listed explorer with licences in north-western Greenland, slid after Mr Trump’s interview. Danish bonds widened marginally against German bunds as traders priced a sliver of geopolitical risk. The moves are small but telling: markets doubt that Brussels can protect Danish assets if Washington turns the screws.

The commission insists it sees no precedent linking Caracas to Nuuk. Ms Pinho told journalists, “Each country may be very interesting from many points of view, but that shouldn’t trigger any interest beyond possible… investments, et cetera, nothing going beyond that.” Such faith in good intentions collides with Mr Trump’s record. He has appointed Jeff Landry, governor of Louisiana, as special envoy to Greenland—an envoy to a territory America does not own. He boasts that the island’s airfields bolster missile defence and its minerals could “keep China out”.

Bruised ideals

Europe’s foreign-policy chief, Kaja Kallas, had spoken to Marco Rubio, America’s secretary of state, about both Venezuela and Greenland. Officials describe the call as “constructive” but offer no detail, citing diplomatic sensitivity. They promise to “remain in close contact with Denmark” and to raise Arctic security at future NATO meetings. It sounds suspiciously like waiting.

We completely stand by Greenland and in no ways do we see a possible comparison with what happened (in Venezuela). — Paula Pinho, European Commission spokeswoman

The broader lesson is grim. When a superpower flexes, the EU preaches procedure and hopes for the best. Eighty years after America liberated western Europe, Brussels still lacks a script for managing the alliance when Washington goes off-piste. Mr Trump has noticed. By coupling the fall of Caracas with a flirtation over Greenland, he tests whether Europeans believe their own doctrines.

Ms Frederiksen vows to “strongly urge the US stop the threats”. Mr Nielsen says Greenland “will not be a piece of property that can be bought by just anyone.” Those statements ring brave, yet they rest on Danish budgets, not European ones. If the union cannot shield a territory whose colonial ties run to its core, its talk of strategic autonomy remains what critics always said it was: a slogan in search of a strategy.