The long-delayed trade deal with the Mercosur bloc is now in a new phase of uncertainty after the European Parliament voted to ask the EU’s top court for a legal opinion. This adds more political and procedural risk to a deal that is already facing a lot of opposition from farmers across Europe.

EU Perspectives breaks down the practical and political consequences of this development.

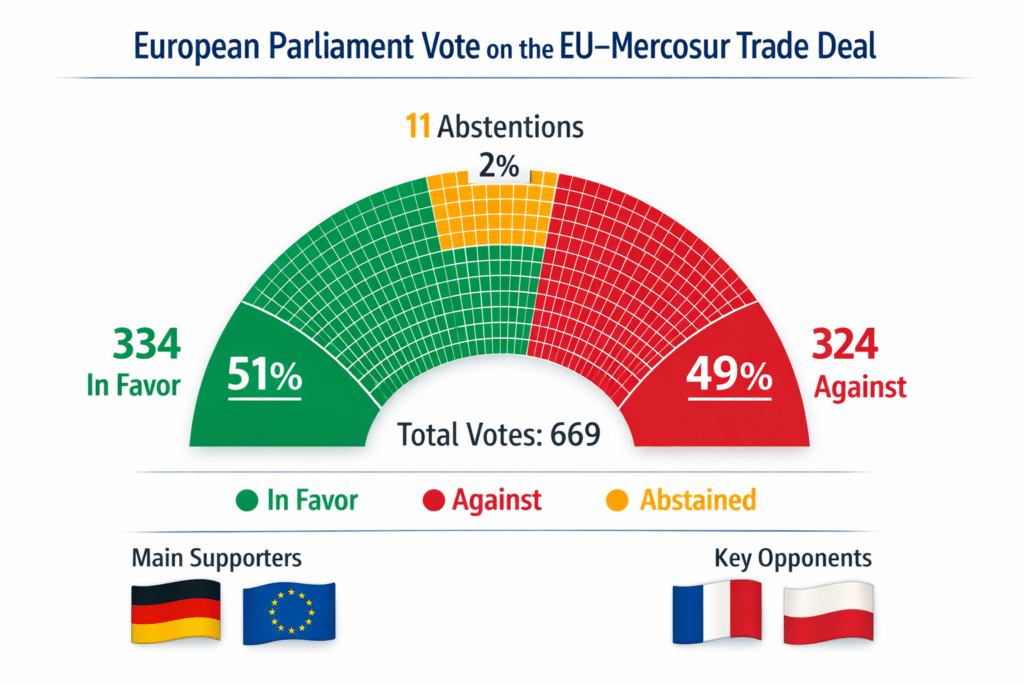

Members of the European Parliament voted 334 to 324, with 11 members not voting, to send the EU-Mercosur agreement to the Court of Justice of the European Union to get their opinion on whether its legal structure follows EU treaties.

The referral is not a lawsuit; it is a formal request for legal clarification. These kinds of opinions are legally binding and can last for up to two years. The vote shows that people are worried about the European Commission’s plan to split the agreement into two parts: a broad political partnership that needs to be ratified by each country and a stand-alone trade agreement that could be used temporarily at the EU level.

You might be interested

The EU–Mercosur Deal: What It Covers

The deal connects Mercosur, which includes Brazil, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay, to the European Union. In 1999, talks about trade started. The trade pillar was finished in 2019, and the political and cooperation chapters were finished in 2020. The two sides came to an agreement on a new package in December 2024, after years of no progress. In January 2026, EU governments agreed to sign it.

The deal would lower tariffs and make it easier for South American agricultural goods to get into the EU market. This would help EU industrial exporters like carmakers and machinery makers.

Why the Legal Structure Is Disputed

Some members of the European Parliament say that the Commission’s “split agreement” method could skip over national parliaments in areas where member states think they should still have a say.

There are also worries about parts that deal with regulatory disputes. Some lawmakers are worried that Mercosur countries might retaliate if the EU makes rules about the environment or consumer health stricter. This could make it harder for Brussels to regulate.

The Commission has defended the approach as legally sound and necessary to avoid further delays, saying that asking a court for an opinion is a well-known way to make sure that the law is clear. The referral makes the ratification process much less certain. A court opinion could push back final approval by as much as two years. The Commission may still want to use trade elements on a temporary basis. If the ruling found discrepancies or legally poorly-resolved issues, it could mean that the parties have to renegotiate or change the legal basis. Any of these outcomes would bring back political arguments that EU leaders thought were over when the deal was signed earlier this year.

Farmer protests raise pressure on politicians

The legal challenge comes at a time when farmers are still protesting across Europe. The Mercosur deal has become a major source of anger in the farming industry.

Farmers say that the EU has stricter rules about pesticides, animal welfare, land use, and following climate rules. They also say that imports from outside the EU may be made under less strict rules and for less money.

People protested outside the European Parliament in Strasbourg before the vote, calling for a delay or cancellation of the deal.

Political Differences in Parliament

EU institutions have tried to ease worries by making safety measures stronger. In December 2025, they reached a consensus to temporarily suspend tariff preferences if EU producers suffered from sensitive agricultural imports from Mercosur.

Critics, on the other hand, say that the measures may take a long time to take effect and be hard to enforce once trade picks up. The close vote showed that there was no stable majority on the issue. Opposition brings together lawmakers who are worried about climate change and deforestation with others who are more concerned with sovereignty, protecting farmers, and keeping institutions in balance.

France and a few other member states have already said they have concerns, especially about how the agreement will affect farming in their countries.

What people in South America think

People in the capitals of Mercosur are closely monitoring the EU’s internal issues. They who support the deal say it is a strategic link between regions, but also warn that long periods of uncertainty could hurt the EU’s reputation as a negotiating partner.

At the same time, Mercosur countries also have to get their ratification, which means that delays in Europe may ease political pressure at home.

Next steps

The court referral doesn’t end the EU–Mercosur agreement, but it does delay its implementation.

The deal is now a test case for the EU in a bigger problem: how to push for more free trade while also enforcing stricter environmental rules and keeping political support in areas like agriculture that are sensitive. The agreement is still signed for now, but it is politically weak, legally unclear, and becoming more contested.