If the EU and its capitals can align their initiatives—PESCO projects, EDF funding, Arctic infrastructure, and an inclusive command architecture—they just might field a self-sustaining force by the early 2030s. The alternative is remaining hostage to the choices of others, friend or foe alike, European and American geostrategy experts agree.

The Greenland landmass sits astride the Greenland–Iceland–UK (GIUK) gap, the North Atlantic sea-lanes that bind North America to Europe. Its mineral riches, including rare-earths, nickel, and uranium, and its unrivalled location for early-warning radars make it the single most valuable piece of real estate in the Arctic.

A forced US takeover—even if only a hypothetical scenario—would therefore reverberate through every European security and economic calculus over the next decade. Such an American posture would enable Washington to dominate the trade routes upon which European trade relies and hold at risk Russia’s Northern Fleet. In a rather shocking development over the past 12 months, such a takeover has been under serious consideration.

The Greenland gambit

Strategically, this hypothetical seizure would transform the military playbook of NATO allies on both sides of the ocean. It would likely involve the air-mobile insertion of US Special Operations Forces onto key airfields and the reinforcement of Pituffik Space Base, which already serves a critical missile-warning role. The deployment of Aegis-ashore and THAAD batteries would create an American ice bubble to screen the GIUK gap.

For Europe, this would erode the assumption of American benevolence that underpins NATO. A generation of European officers would have to plan for a potentially hostile US alongside a revisionist Russia and a systemic rival in China.

You might be interested

The motivations behind such American assertiveness have their roots in a fundamental shift in grand strategy. As noted in the Journal of European Integration, there is a prevailing consensus in Washington that the US must engage in great power competition with China. This shift has led American defence planners to prioritise the Indo-Pacific, resulting in a relative downgrade of Europe.

The price of alignment

US views on European unity depend on two interrelated factors: cost tolerance and expected alignment. Washington has traditionally supported European unity to counter Soviet and Russian threats, but it has resisted moves that might challenge American influence or its preferences on China. This dual objective of supporting integration to build a more capable partner while managing it to preserve US influence has shaped the transatlantic relationship since the early Cold War.

450 million Europeans should not be begging 340 million Americans to protect Europe from 140 million Russians who cannot take on 38 million Ukrainians. — Andrius Kubilius, EU defence commissioner

US support for economic integration was originally motivated by the belief that a resilient Western Europe would better resist Soviet influence and reduce the need for American involvement. However, by the mid-1950s, Washington concluded that integration could only succeed when coupled with a strong US security commitment. Over time, what began as a temporary expedient evolved into a structural feature of the alliance.

According to the Journal of European Integration, American policymakers use binding strategies to secure loyalty through positive inducements or coercive measures. When expectations regarding European alignment are negative, the US is likely to raise the exit costs of the alliance.

The era of ‘coercive binding‘

During the first administration of US President Donald Trump (and even more so the current one), the White House operated on the premise that the US was globally overcommitted and undercompensated. This resulted in a modus operandi of coercive binding. Mr Trump treated trade imbalances as a threat to American self-sufficiency and viewed European integration not as a strategic investment, but as a potential liability that could diverge from American policy on China.

Unlike his predecessors, Mr Trump questions the very value of the alliance and openly criticised its relevance to the US. While previous administrations had on occasion taken protectionist measures to shield specific sectors of the economy, Mr Trump treats trade imbalances more broadly as a profound threat. Rather than seeing European integration as a strategic investment, his administrations have increasingly treated it as a mere liability.

This American perspective views a more autonomous and economically united Europe as problematic. Washington fears that a united Europe might act as a substitute trade partner for Beijing or compete in key technological industries. The Journal of European Integration explains that Europe’s technological-industrial base, if it becomes too competitive, could erode American technological superiority.

A liability in the Atlantic

This would make it more difficult for Washington to maintain the edge in high-end military capabilities upon which its conception of warfare is dependent. Consequently, American diplomacy has at times framed European defence rules as discriminatory poison pills designed to exclude American firms.

Europe’s policies on advanced technologies have long been a concern for Washington not just economically, but also strategically. Europe has been an important market for selling US innovative technologies, which drives the overall competitiveness of the US tech ecosystem.

European NATO countries together employ 1.4 times more personnel than the US, while still generating less combat power. — Erik Stijnman, senior research fellow at Clingendael

This feeds into the US defence industry. The US military relies on advanced technologies developed through access to European markets for economies of scale. European competition could reduce US leverage and complicate efforts to counter Beijing. In this sense, European unity—if not clearly subordinated to US strategic aims—is perceived as obstructive.

The costs of exit

To limit European actions that could undermine US strategy, the Trump administration relies primarily on coercive binding strategies. Mr Trump issues direct threats and warns of negative consequences, such as decreases in security cooperation, if European countries failed to comply with demands.

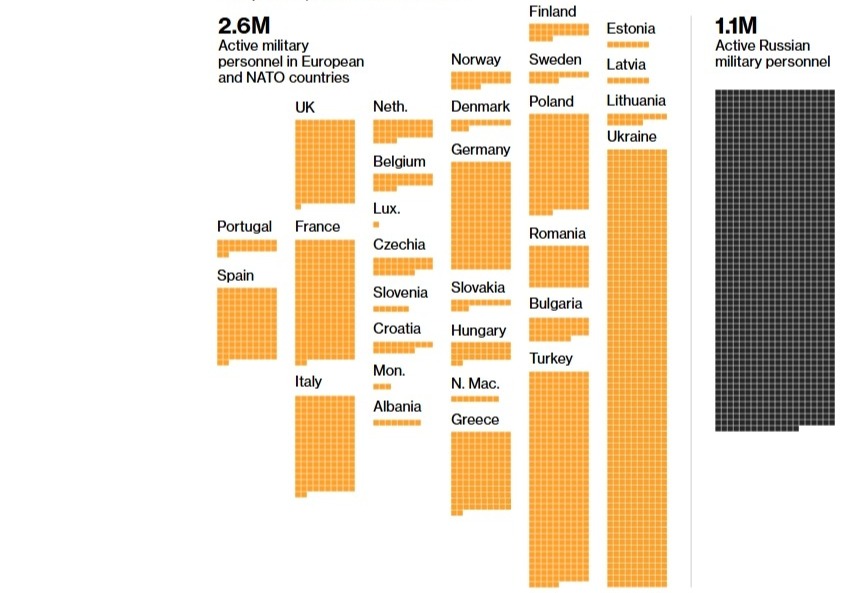

While Washington debates its level of commitment, Europe remains militarily weak. Erik Stijnman, Army Lieutenant Colonel in active Dutch Service and senior research fellow with the think-tank Clingendael’s Security unit analyses the European military imbalance. He argues that Europe possesses too much tail and not enough teeth (and likes to quote Andrius Kubilius, EU defence commissioner, as saying that “450 million Europeans should not be begging 340 million Americans to protect Europe from 140 million Russians who cannot take on 38 million Ukrainians“).

During the Hague NATO summit, nations decided to allocate at least 3.5 percent of GDP to core defence requirements. However, Mr Stijnman questions why performance is measured by spending percentages rather than capabilities. He notes that most European countries are ramping up spending in a linear, incremental manner, buying more of the same equipment based on existing assumptions. This approach will not necessarily deter opponents or win future wars. Spending €800bn on the European ReArm ambition should make us mindful of the fact that taxpayers’ money will not be spent on healthcare, education or housing.

Rethinking military productivity

Mr Stijnman points out that solely adding funds will not repair a poor ratio. (To measure a force’s might, it is common to compare combat troops to supporting personnel, known as the tooth-to-tail ratio.) In the Netherlands, there are less than 44,000 active servicemen, of whom only 8,000 serve in combat roles. Another 25,000 civilian personnel support these forces, resulting in a poor 1:8 ratio. European NATO countries together employ 1.4 times more personnel than the US while still generating less combat power.

Discussions on a potential European-led mission into Ukraine proved to be a wake-up call. Europe was unable and unwilling to deploy troops in sufficient numbers without an American backstop.

Mr Stijnman deconstructs the routine arguments for a larger tail. While technological advancements are often blamed for increased maintenance and ICT needs, the Dutch strategist argues they also provide opportunities to decrease the tail. Faster intelligence dissemination using AI models and Large Language Models should result in improved decision-making speed.

Defining strategic autonomy

This would warrant flattening the chain of command and reducing headquarters sizes. Mr Stijnman suggests that military labour productivity should be regarded as the ratio of soldiers to the number of unmanned or autonomous vehicles. Linear spending will neither generate better teeth nor a more effective tail. To deter opponents to enter the ring in the first place or to knock them out when needed, both goals need to be achieved.

The Clingendael Institute defines European Strategic Autonomy (ESA) as the ability of Europe to make its own decisions and have the necessary means to act upon them. In their report, European Strategic Autonomy in Security and Defence, the authors state that ESA is the ability to act—together when possible, alone when necessary.

They describe Europe as militarily weak, leaving it ill-suited for a world marked by Russian revisionism and a less predictable US. The report faults political will, not legal barriers, for inaction, noting that Article 44 of the Treaty on European Union—which allows entrusting missions to coalitions of the willing—has never been used. “Constructive abstention” is recommended to bypass unanimity hurdles.

Most EU members still regard NATO as the backbone of collective defence; ESA must therefore grow in complement to, not in competition with, the Alliance. The authors propose embedding the EU’s eventual military level of ambition inside the NATO Defence Planning Process.

The 50 per cent benchmark

The Clingendael authors propose that European NATO members should collectively deliver 50 percent of NATO’s force-planning targets. This numeric split would supply a concrete burden-sharing benchmark. Closing key European shortfalls in strategic lift, precision fires, and missile defence would require significant multibillion-euro outlays sustained for a decade.

Without this, Europe will continue to possess only about 10 percent of high-end American capacity despite spending roughly one-third of the American defence budget. Strategic obstacles to a joint military force are numerous and deeply rooted in national differences. Divergent political will and threat perceptions mean that eastern states prioritise Russia, while southern states focus on the Middle East and North Africa.

European Strategic Autonomy is the ability of Europe to make its own decisions, and to have the necessary means, capacity and capabilities available to act upon these decisions. — The Clingendael Institute

Budgetary and industrial fragmentation persists, with 27 different research and development cycles. The Clingendael report notes that Europe’s defence market remains fragmented, which drives up unit costs. Furthermore, only France and the United Kingdom possess nuclear weapons, and there is no shared doctrine for their use in a joint European context.

Further obstacles include the third-country status of key partners. The United Kingdom cannot sit in PESCO by default, and Norwegian and Swiss participation remains limited. The iInstitute urges incremental culture-building measures, such as joint schools and multinational headquarters, to narrow the gap between France’s global outlook and Germany’s focus on crisis management.

Internal friction

There are also legal and constitutional constraints; countries like Ireland and Austria maintain neutrality clauses, and Germany requires a parliamentary veto on military deployments. Public opinion and fiscal ceilings also play a role. Competing social spending and debt rules hinder investment. The Commission’s 2025 “Plan to Rearm Europe” proposes an €800bn off-budget vehicle to address this. Success is uncertain because of divergent strategic cultures. France sees ESA as existential, a prerequisite for agency and for becoming a revitalised ally within NATO. Germany endorses more capability but prefers incrementalism. Poland prioritises the American security guarantee and views ESA warily if it threatens to dilute US engagement.

All of the above notwithstanding, building this self-reliant capacity is the only way to deter great powers that contest European sovereignty in the Arctic and beyond. Europe must either become the author of its own security or remain a geopolitical dwarf. The choice is for the Europeans to make, and the time for making it is running out as the strategic environment grows ever more contested; just ask the Greenlanders.