In late September, the Dutch government took an extraordinary step by placing semiconductor manufacturer Nexperia under curatorship and forcing out its Chinese chief executive. Since then, the story has grown into a larger-than-life cautionary tale.

Within days, the crisis escalated. What began as a Dutch corporate-governance intervention became a geopolitical confrontation, exposing Europe’s vulnerabilities in an economically interdependent world where economic security and geopolitics increasingly overlap. There are lessons to learn.

1. EU-wide consequences of national decisions

Despite decades of integration, a single member state can still make decisions with continent-wide consequences. When the Dutch government placed Nexperia under curatorship, it did so using a Cold War–era law laying dormant until then. The move was based on what the Dutch minister of Economic Affairs Vincent Karremans described as overwhelming evidence that the Chinese CEO was preparing to transfer intellectual property, patents and production capacity to China. The goverment conducted the operation in secrecy, without prior consultation with European partners.

The minister justified his unilateral move on the grounds that wider coordination would have increased the risk of leaks and allowed the transfer to complete before any action could take place.

Yet the decision had direct impacts far beyond the Netherlands. Within days, China retaliated by halting chip exports from the Chinese factory that produces the majority of Nexperia’s output. European carmakers warned of production cuts, with Japanese and American manufacturers affected as well. Only after the shock became visible did intensive coordination at EU level begin.

You might be interested

Critics also argued that the unilateral move lacked a broader strategic vision, especially since Nexperia operated not only under the influence of its Chinese owner Wingtech but also that of existing US trade restrictions on the company. “A European response was necessary, because EU member states on their own cannot respond to the first and second largest economies in the world,” said Dutch Member of Parliament Laurens Dassen of the pan-European party Volt.

2. Low-tech ≠ non-strategic

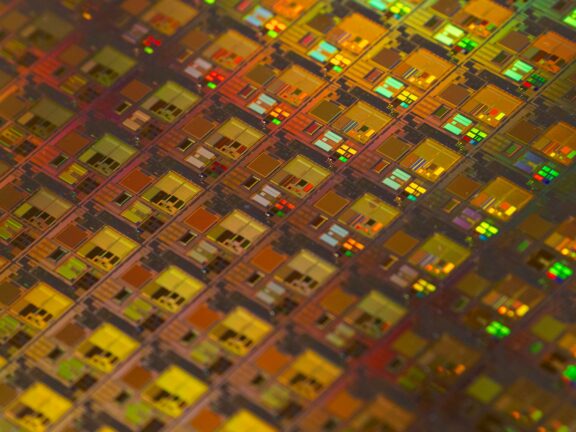

Europe’s dependence on China does not only concern advanced technologies; it extends deeply into the most basic components of modern life. Nexperia’s chips are not cutting-edge. They do not power artificial intelligence models or supercomputers. Yet without them, nobody can assemble a single car. The automotive industry consumes more than 12 per cent of global semiconductor output, and it relies heavily on precisely the kind of cheap, standardised components that China produces at scale.

Because these chips are inexpensive, manufacturers keep only minimal inventories and organise production on a just-in-time basis. This makes the system efficient in normal times — and extremely fragile in a geopolitical crisis. Even a short disruption can force factories to slow down or shut entirely, as happened during the pandemic and again during the Nexperia saga.

“Shortages of the type of simple chips used in the control units of vehicle electrical systems are hitting automakers around the world hard, including here in Europe,” an ACEA statement read in late October. “Many alternative suppliers exist, but it will take many months to build up the additional capacity needed to meet the shortfall in supply. The automotive industry does not have long before it feels the worst effects of this shortage.”

A European response was necessary, because EU member states on their own cannot respond to the first and second largest economies in the world. — Laurens Dassen, Dutch MP

Strategic vulnerability is thus not confined to cutting-edge technologies. Standard components can be just as critical when production concentrates geographically and inventories are short.

European industrial policy has traditionally focused on advanced semiconductors and frontier innovation, while dependencies in lower-margin components have attracted less attention. The temporary disruption of Nexperia’s exports showed that these “low-tech” parts are difficult to replace at short notice. When supplies were interrupted, the resulting leverage became visible almost immediately.

3. Interdependence, a tool of power

“Everything can be weaponised,” Maroš Šefčovič, European trade commissioner told Euronews in the aftermath of the dispute. “It started with [Russian] gas, then it continued with critical raw materials and high and low-end chips. It can all be weaponised.”

Economic interdependence has become a weapon. China’s industrial strategy of dominating critical technologies and supply chains does not only capture market share, but also generates political leverage. Control over production enables control over outcomes. Export restrictions, payment demands and selective enforcement of rules are all instruments in this strategy.

Everything can be weaponised. — Maroš Šefčovič, European trade commissioner

The response to the Dutch intervention followed a familiar pattern. Rather than challenging the measure in court, Beijing acted through administrative power: seizing control of production, halting exports and applying pressure until costs became unbearable for European partners. Similar tactics have been used before, against countries as diverse as Norway, Lithuania, and Australia.

Europe, by contrast, still prefers to operate through legal frameworks, trade agreements and multilateral institutions — many of which are increasingly ineffective in a world where great powers act unilaterally.

4. Europe is divided. Others know

With little material bargaining power, tough rhetoric won’t do much to impress Beijing either, China expert Frans-Paul van der Putten told Dutch newspaper NRC. “Europe is tying its own hands.”

Europe’s internal divisions are exploitable. In the Nexperia crisis, national interests quickly overrode collective ambition. Countries with large automotive sectors, such as Germany, pressed for a rapid resolution. Others prioritised trade in unrelated sectors. Longstanding calls for strategic autonomy dissolved under the pressure of immediate economic pain.