The European Union’s €653m-a-year agricultural support scheme for its outermost regions shows immediate visible benefits but fails to provide value for money in the long term, a new audit by the European Court of Auditors (ECA) concludes.

When asked how the Court would judge the overall performance of the Programme of Options Specifically Relating to Remoteness and Insularity (POSEI), Céline Ollier, head of task for the audit, said the scheme provides meaningful support and has allowed some traditional sectors to remain competitive. Beyond short-term income support, however, the programme, she added, does not sufficiently address long-term sustainability, especially regarding climate adaptation and resilience.

The auditors’ assessment, published this week, exposes a dilemma that is familiar in EU agricultural policy: that of trying to promote income stabilisation while making essential structural changes. In the case of the outermost regions, which face permanent handicaps from their remoteness, their insularity and their dependency on imports, the Court concludes that POSEI has been a priority over adaptation with positive effects.

Why do some sectors survive while others fail?

The audit shows different outcomes in different regions and sectors, so what explains POSEI’s uneven impact? Answering that question, Ollier identified the relevance of market structure and external competition.

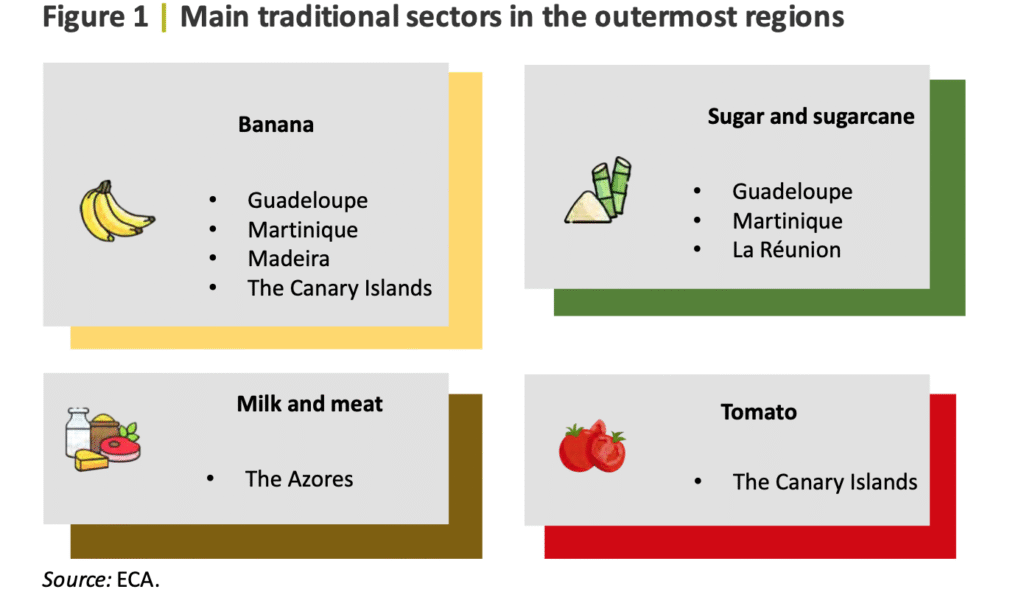

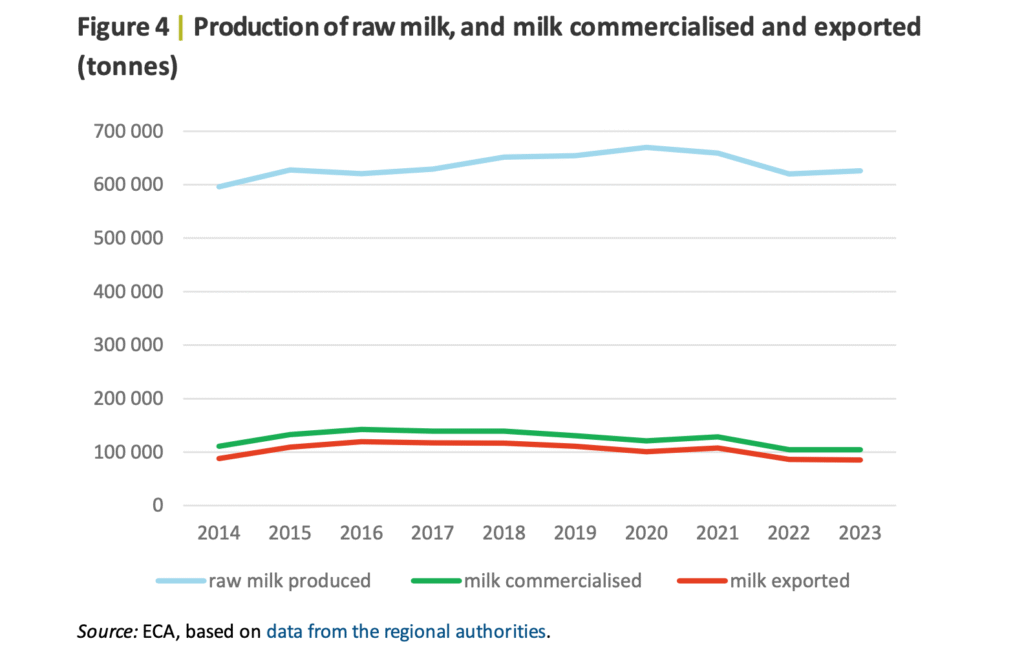

In the Azores, POSEI has allowed the continuation of a competitive milk sector. The islands face limited competition from third countries, and a significant share of its milk is allocated to the production of high-value products such as cheese for export to the Portuguese mainland. Retail prices for Azorean milk are also comparable to those of mainland products, suggesting that POSEI has eliminated any potential price gap from being an outermost producer.

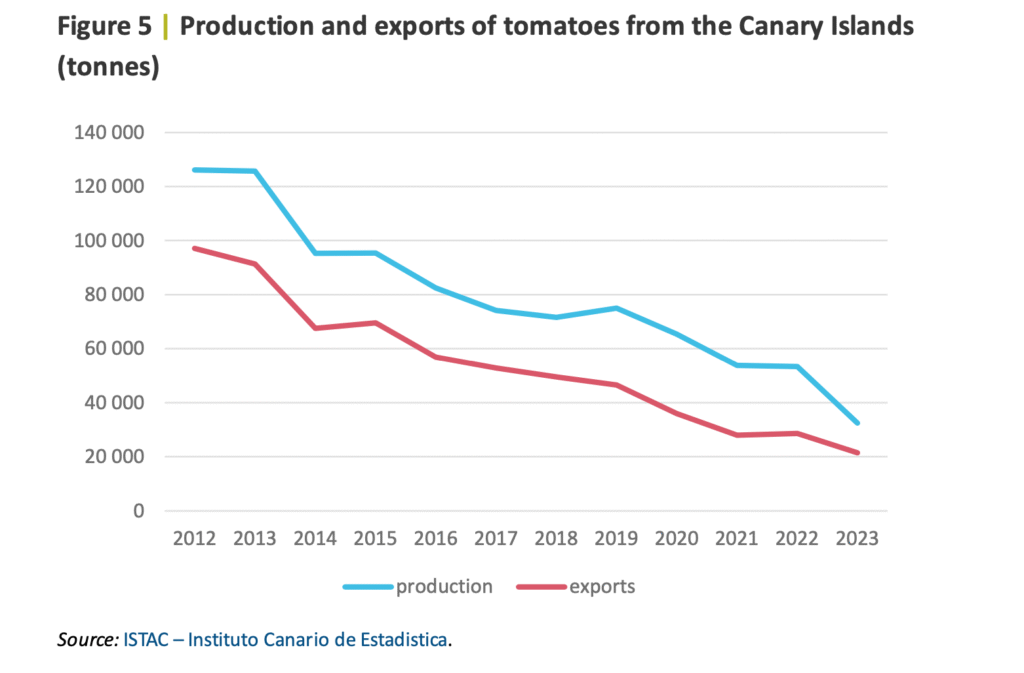

By contrast, tomato production in the Canary Islands continues to decline despite sustained EU support. Auditors have attributed this to fierce competition from Moroccan tomatoes, which have favourable geographical proximity to European markets and low production costs. Canarian tomatoes also lack a specific quality label to distinguish them from others on the market, so retail prices for these products are uncompetitive with those from mainland or third country producers.

As these contrasting examples illustrate, Ms Ollier concluded, the Programme of Options Specifically Relating to Remoteness and Insularity works better for sectors that can avoid competition or improve their standing in the market—factors that do not apply uniformly across all the outermost regions.

Earmarked funding reflects historical priorities

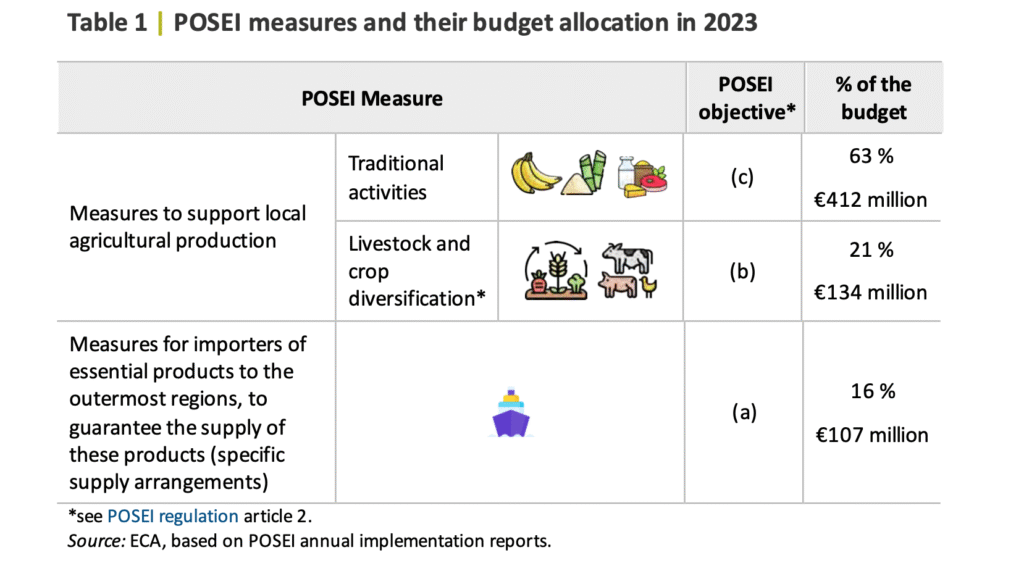

Does POSEI distribute its funding between sectors in a way that reflects today’s policy priorities? The audit suggests it does not. Almost two-thirds of POSEI funding stream—€412m a year—goes to traditional agricultural sectors. A mere 21 per cent is allocated for other agricultural activities, with another share being used to subsidise the imports of essential items the populations of the outermost regions need.

This distribution mainly reflects historical factors. As Ms Ollier explained, when it was created in 2007, POSEI’s budget ballooned by nearly €300m when the then-existing agricultural programme’s funding was transferred to other EU programmes. The banana sector was included at the same time, and to this day, around 42 percent of total POSEI funding—€277m—still goes to it even when cultivated areas and production figures have dropped in some regions.

You might be interested

The allocation for bananas has not been adjusted, she noted. Auditors caution that funding POSEI in this way encourages the discouragement of diversification and perpetuation of support for sectors that are declining.

Climate adaptation does not feature

How well does POSEI do regarding climate-related issues? The answer is emphatic. The scheme has been around since 1990 but still does not sufficiently address climate-related risks, even though the outermost regions’ exposure to extreme weather events is increasing rapidly.

POSEI funding has promoted investments in monoculture permanent crops with little focus on crop rotation or diversification in the outermost regions, both of which improve resilience and are vital for the long-term health of specific soils. The concentration of agricultural lands dedicated to these permanent monocultures, auditors note, fosters long-term land vulnerability and increases environmental pressure on the land.

Some forms of conditionality have been applied to avoid this situation—for example, in France’s outermost regions POSEI supports a sustainability plan that farmers must adhere to but other requirements are still limited. At the same time, POSEI rules permit farmers to receive aid payments based on estimated yield foregone due to adverse conditions. Auditors argue that these rules and mechanisms favour income stabilisation in situations where farmers face increasing challenges such as droughts, storms and cyclones.

Unsustainable future prospects under CAP reform

The audit was conducted as negotiations were under way over a new Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) due to take effect after 2027. Under the proposed regulation the European Commission is currently negotiating, the POSEI regulation would be repealed and there would be no earmarking of funds for agricultural support in outermost regions.

Support for agriculture in outermost regions would be subsumed under an other regime that includes a commitment to the development of a policy framework at European Union level with an explicit chapter on outermost regions. Under this framework, it would be stated as an EU Union priority but Ms Ollier says the framework appears to place less emphasis on traditional sectors for which other levels of support could be granted. There is also a requirement that direct payments be distributed more equitably among farmers. It is still uncertain whether funding would be available at its current rate.

For the Court, this CAP reform agenda raises strategic issues. In the absence of an explicit commitment to diversification, climate adaptation and ensuring that agriculture in outermost regions is viable in the long term, auditors warn that EU support for those regions may keep them bound to economic structures that no longer serve them well in a changing global environment.