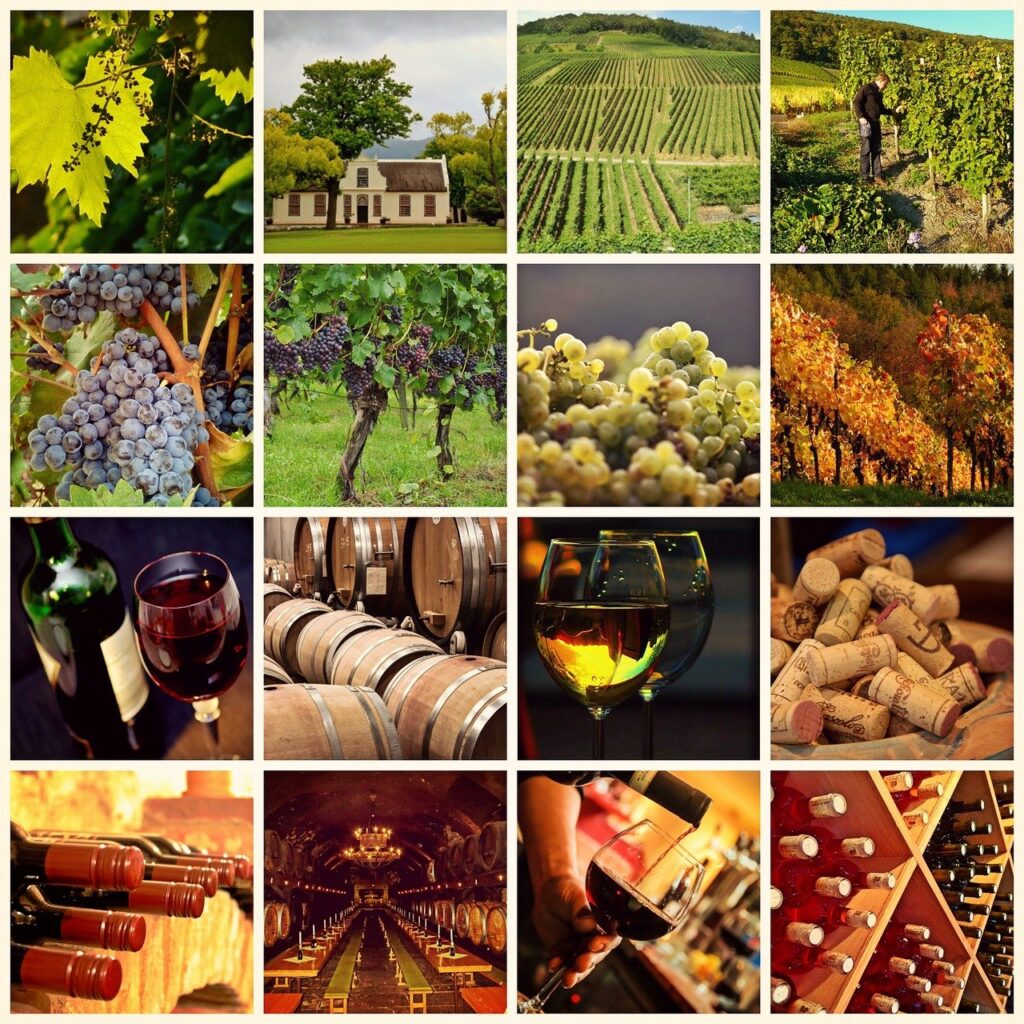

The EU’s ‘wine package’ reached the European Parliament plenary this week as an emergency toolkit for a sector squeezed by falling demand, shifting tastes, climate stress and trade uncertainty. After a fast-tracked run that ended in a 4 December 2025 political agreement, MEPs signalled a clear pro-package majority — but the debate also surfaced a sharper cultural fault line over what ‘saving wine‘ should mean in practice.

At the heart of the file was a targeted rewrite of EU market rules and support measures for wine and aromatised wine products. The goal was to give member states more flexible crisis tools, tighten and harmonise labelling, and help producers adapt — including by developing lower- and no-alcohol categories and reaching new markets. The Commission presented the package in March 2025, debated it Monday and voted less than 24 hours later.

The result? Parliament approved the provisional agreement reached with EU member states on 4 December 2025 by 625 votes to 15 with 11 abstentions.

The new set of rules will address challenges that wine producers are facing and unlock new market opportunities.

You might be interested

Fast law for a fast-moving crisis

Rapporteur Esther Herranz García (EPP/ESP) presented the compromise as a quick, pragmatic response to “the crisis that the wine sector is facing”, arguing that Parliament had added measures to strengthen what she called an already “positive” proposal. She highlighted the compressed timetable: three weeks of technical talks followed by a 4 December 2025 political agreement, later backed unanimously in the Agriculture Committee.

Her rundown of Parliament’s changes focused on supply management, fairness across member states, and clearer rules. She said MEPs removed the 2045 end-date for planting authorisations, and for the first time enabled permanent grubbing-up of vineyards to be financed via EU sectoral funds — framed as a way to create “equality of opportunity” while avoiding “the permanent abandoning of wine growing”. She also cited export and SME-oriented steps: standardised export labelling; promotion campaigns extended up to nine years with higher co-financing for small operators; and a definition of foreign markets allowing large markets to be split regionally.

Uprooting vines, reshaping the market

One sensitive point was how to describe lower-alcohol products. Ms Herranz García said the compromise replaced the Commission’s earlier “light in alcohol” wording with “low alcohol”, while other MEPs pushed for “reduced alcohol” terminology — reflecting a broader political and regulatory struggle over how such wines should be defined and marketed. The final rules ultimately use the categories “alcohol-free” and “alcohol-reduced”.

Commissioner for Agriculture Christophe Hansen told MEPs the package aimed to “urgently provide much-needed support” amid “unprecedented challenges” — declining demand, changing consumer preferences, climate impacts and a volatile international context. He credited Parliament for moving quickly to a compromise and warned that the pressures “persist and in some cases have even intensified.”

The Commission’s balancing act

Mr Hansen pitched the measures as a two-track toolbox: instruments to address structural oversupply in some regions, and rapid-response tools for shocks linked to “climatic or market events”. He also argued the package helps producers adjust to demand by facilitating lower-alcohol wines and improving labelling for consumers, including for aromatised wine products. On competitiveness, he pointed to higher support rates for producer organisations and climate-adaptation investments, plus an expanded scope for wine tourism beneficiaries.

He flagged one element the Commission accepted only “in the spirit of compromise”: price guidance for bulk wines. While he said he understood the intention, he warned it “has to be managed with care” and urged reliance on existing oversupply tools that limit volumes “and don’t entail these risks.”

A majority — with nerves underneath

Across the mainstream groups, the debate reinforced expectations of a comfortable majority. EPP speakers argued the package answered cost pressures, shrinking consumption and tariff risk, including through promotion and by developing alcohol-free and lower-alcohol categories.

ECR’s Carlo Fidanza (ITA) backed the compromise as “a clearly positive result” that boosts competitiveness, crisis management and export promotion, and he highlighted clearer definitions for non- and low-alcohol wines as a way to open new market segments. Greens speakers, while broadly supportive, pressed harder against “business as usual” and for more innovation, climate-suited varieties and easier access for small producers to promotion tools.

Sour grapes

The sharpest resistance came from Patriots speaker Gilles Pennelle (FRA), who cast the crisis in civilisational terms and rejected two pillars of the compromise outright: grubbing-up “is absolutely not a solution”, he argued, and “removing alcohol from a product and continuing to call it wine” was cultural dilution, not adaptation. Other criticism focused less on symbolism and more on distribution: one MEP warned that the package risks favouring large producers while smaller and medium-sized growers remain burdened by bureaucracy, describing the approach as dangerously disconnected from realities on the ground.

Heritage, identity and the backlash

Closing the debate, Ms Herranz García urged adoption so the tools could take effect quickly, while noting that other ideas — including more budget flexibility within years and possible use of the crisis reserve for grubbing-up — would likely return in the post-2027 CAP review. In the end, the vote will decide not only whether the compromise becomes law quickly, but also how the EU frames its response to the downturn — either as crisis management and adaptation, or as the opening chapter in a longer political argument about what, in 2026, Europe is willing to call “wine.”

The legislation still requires formal approval by EU member states in the Council before it can enter into force, after which the new rules will begin rolling out through national CAP programmes and sectoral support measures.