In technological innovation, Europe has long lost ground to its global rivals. US tech giants dominate the digital economy, while China leads in sectors such as robotics and advanced manufacturing.

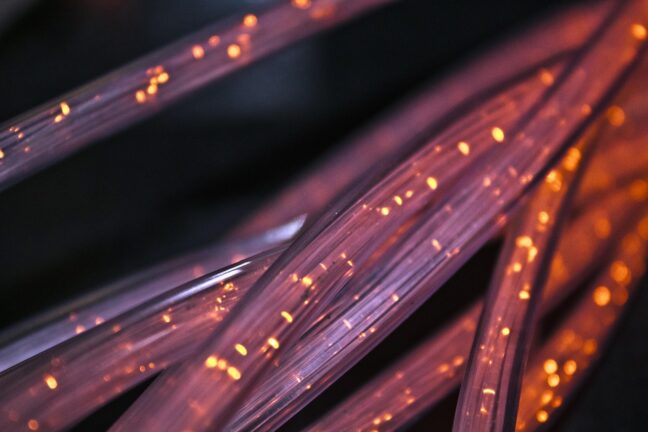

Germany’s Ifo Institute, one of the country’s largest economic think tanks, warns of the “mid-tech trap” Europe finds itself in. With its economy leans heavily on industries such as automobiles and telecommunications while lagging in cutting-edge sectors like semiconductors and robotics. Subsidies meant to drive innovation have so far failed to close the gap.

The EU has long lagged behind the US in technology. Only four of the world’s top 50 tech companies are European, and no European company with a market value above €100bn has been founded from scratch in the past 50 years. In contrast, the six US companies (Microsoft, Apple, NVIDIA, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, and Meta) with a value of above $1tn, all tech companies, were created in this same period.

In European industry, mid-tech sectors continue to post the highest productivity growth. Among the 10 technology sectors with the fastest productivity gains in the five largest euro area countries, only the Dutch pharmaceutical industry qualifies as high-tech.

You might be interested

This has resulted in a widening productivity gap between the EU and US. Between Q4 2019 and Q2 2024, labor productivity per hour worked rose by just 0.9 per cent in the eurozone, compared to 6.7 per cent in the United States.

Europe is falling further behind in high-tech areas such as the digital economy – Clemens Fuest, Ifo Institute

Quantitative and qualitative underfunding of innovation

In 2023, former ECB President Mario Draghi warned in a European Commission report about Europe’s declining productivity and global competitiveness, citing an underdeveloped capital market, underinvestment, and a fragmented internal market. “Europe must profoundly refocus its efforts on closing the innovation gap with the US and China, especially in advanced technologies,” Draghi urged.

But the problem is not just the amount that Europe invests in research, but how it spends it, economists from France, Germany, and Italy, including Nobel laureate Jean Tirole (Toulouse School of Economics), Clemens Fuest (Ifo Institute), and Daniel Gros (Bocconi University) argue in a joint report. “EU research investment is concentrated in the automotive industry and similar sectors, while Europe is falling further behind in high-tech areas such as the digital economy,” says Fuest. And despite the fact that the automotive sector has always received a large share of Europe’s innovation funds, even this industry now lags behind Chinese manufacturers in key innovations.

Over the past decade, Brussels has invested roughly €100bn in technology programs, mainly through Horizon Europe (€11–12bn per year). But according to the report, projects are often planned in a top-down fashion and shaped by national interests. As a result, “less than five per cent of Horizon Europe supports breakthrough innovation”, the economists found. Instead, many funds end up with large corporate consortia and bypass smaller enterprises, resulting in incremental business improvements rather than transformative breakthroughs. The report therefore argues that more decision-making power in terms of funds allocation should be granted to scientists and engineers, and fewer civil servants.

Europe must profoundly refocus its efforts on closing the innovation gap with the US and China, especially in advanced technologies. – Mario Draghi, former president of the European Central Bank

Efforts to close the gap

To address some these shortcomings, the European Commission launched the public-private “EU Startup and Scaleup Strategy” in late May, “a clear statement of purpose: to make Europe the best place in the world to start and grow a business,” according to the Commission. The €10bn initiative aims to help tech companies scale rather than stagnate or relocate abroad, particularly to the US.

Part of the “Choose Europe to Start and Scale” strategy, the plan seeks to close Europe’s “unicorn gap”; its shortage of startups valued at over $1 billion. The plans should tackle problems such as fragmented regulation, limited access to finance and talent, and inadequate infrastructure. The fund will invest directly in promising companies, with EU public capital complemented by private funding. Measures include simplified rules for high-tech startups, faster access to public procurement, and streamlined entry procedures for non-EU founders.

While the plan was broadly welcomed, industry leaders stressed that clear timelines and stronger steps toward a capital union are essential to truly close the gap with global competitors.

As the European Business Angel Network put it: “Building a vibrant angel and startup ecosystem in Europe is not just strategically important, but an economic necessity in the face of intensifying global competition.”