US President Donald Trump has announced a 100 per cent tariff on foreign-made semiconductors, a move that could strain the recently signed EU–US trade deal. The measure is framed as an effort to bring semiconductor manufacturing back to American soil, but its implications for European technological sovereignty are significant.

The tariffs will not apply to companies producing semiconductors in the United States or committing to do so, sparing major players like Apple, Nvidia, Samsung, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company. Nevertheless, the levy is expected to raise prices for electronics, automobiles, household appliances, and other goods for US consumers—and casts a shadow of uncertainty over the EU-US trade deal.

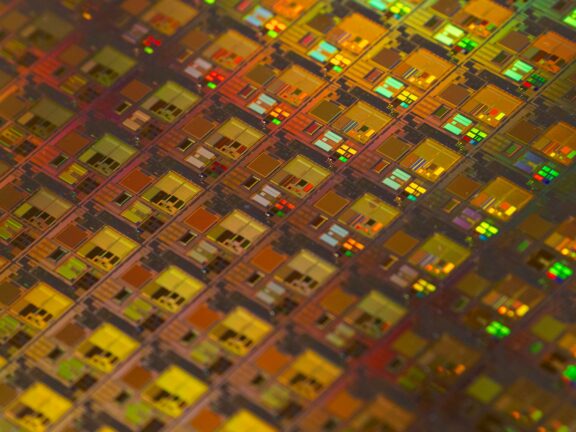

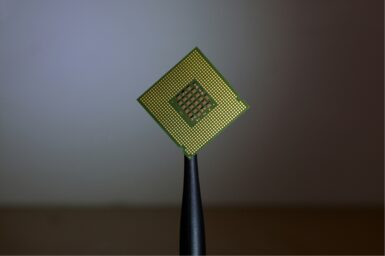

Semiconductors are materials with electrical conductivity between that of a conductor and an insulator. Their ability to switch between conducting and blocking electricity makes them the foundation of microchips, which power computers, phones, cars, and industrial machinery. This makes them critical to modern economies and national security.

The impact on EU trade

Trump’s announcement comes just weeks after Brussels and Washington finalised a trade deal setting a 15 per cent ceiling on US tariffs for EU goods, including semiconductors. Valued at an estimated €700bn in energy purchases and €40bn in AI chip procurement, the agreement was designed to stabilize EU–US economic relations. In theory, EU-made chips should remain protected from Trump’s 100 per cent tariff.

Days after the announcement, European Commission spokesperson Olof Gill reiterated the 15 per cent tariff limit on semiconductors in a post on X, underscoring that the trade deal remains in effect.

You might be interested

The EU chips act

The Trump administration frames the tariff as a national security measure, reflecting longstanding US concerns over dependence on Asian, particularly Chinese, supply chains for critical technologies.

US AI chips will help power our AI gigafactories and help the US maintain its technological edge. — Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission President

Europe faces similar challenges. Currently, the continent accounts for just 10 per cent of global chip production. In response, the European Chips Act, adopted in 2023, aims to double EU market share to 20 per cent by 2030, through €43bn in public and private investments, new gigafactories, and expanded research partnerships.

Nevertheless, with trade deal negotiations concluded, EC Commission President Ursula von der Leyen affirmed that EU companies would continue purchasing the components from American suppliers. “US AI chips will help power our AI gigafactories and help the US maintain its technological edge,” she said.

Digital regulation disputes

The semiconductor debate unfolded alongside growing tensions over digital regulation. On the same day that Trump announced the 100 per cent tariffs, Reuters reported that the US administration had instructed diplomats in Europe to lobby against the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA), arguing that the law stifles free speech and imposes compliance costs on American tech companies.

Simultaneously, US House Judiciary Committee Chair Jim Jordan conveyed negative feedback from congressional meetings in Europe. He noted that “nothing we heard in Europe eased our concerns about the Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act, or Online Safety Act.” He also warned that these measures could create a chilling effect on free expression and threaten the First Amendment.

“Nothing we heard in Europe eased our concerns about the Digital Services Act, Digital Markets Act, or Online Safety Act” — Jim Jordan, US House Judiciary Committee Chairman

European officials struck a more conciliatory tone. Henna Virkunen, Commission Vice-President for tech, emphasised on X that the two sides “had a constructive discussion on how to promote digital innovation, AI and regulate this field smartly.”

These statements followed earlier criticism in July, when Mr Jordan released a report titled “The EU Censorship Files” just days before the conclusion of the EU–US trade deal. In it, he argued that the DSA could compel American platforms to censor political content for users worldwide.

Complex transatlantic deal

Trump’s 100 per cent semiconductor tariffs shed light on the fragility of transatlantic trade and technology relations. The measure aims to bring chip production back to the US. For Europe, this situation raises concerns about technological sovereignty, particularly given the EU Chips Act’s goal of reducing dependency on foreign suppliers for critical technologies.