Alphabet’s Google distorted competition in the digital advertising sector, known as adtech, by favouring its proprietary ad exchange, AdX, and steering ad placements toward its own platforms. This is what the European Commission said when it fined the US tech company €2.95bn last week. How does it work, and how to fix it?

“Google abused its dominant position in adtech, harming publishers, advertisers, and consumers,” said Commissioner Teresa Ribera. The consequences go beyond penalties: Google has been ordered to propose structural remedies, potentially including the sale of parts of its adtech business, to remove the conflict of interest built into its operations. The company has 60 days to submit a plan for approval.

How Google runs the digital ad market

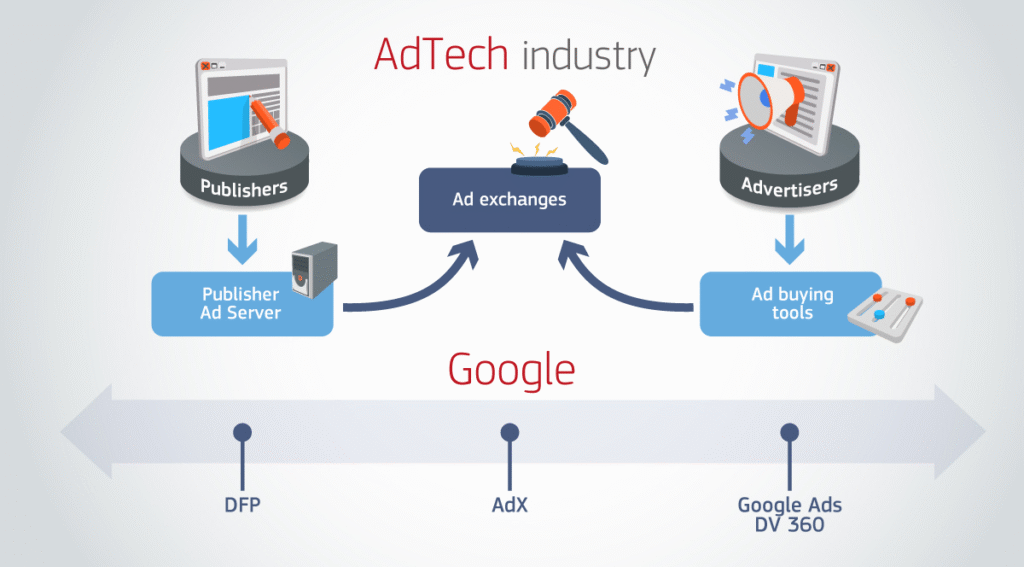

To understand the scale of Google’s influence, it helps to break down the adtech ecosystem. Publishers use ad servers to manage space on their websites. Advertisers rely on programmatic tools to automate bids. And ad exchanges act as real-time marketplaces, matching supply and demand.

Google operates components across all three layers. It runs the ad buying tools Google Ads and DV360, the publisher ad server DoubleClick for Publishers (DFP), and its own ad exchange, AdX. By informing its ad exchange of the highest bids from competitors and programming its buying tools to favour its platform, Google ensured its exchange remained the default choice, sidelining rivals.

The Commission concluded that “Google abused such dominant positions in breach of Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union”.

That is not a functioning, competitive market. It’s a monopoly rent-extraction machine. — Cori Crider, senior fellow at the Open Market Institute

A “monopoly rent-extraction machine”, called it lawyer Cori Crider, senior fellow at the Open Market Institute. As a consequence, “advertisers face inflated costs, publishers see their revenues drained, and consumers ultimately bear the hidden burden. The opacity of the system means only Google knows where the money goes.”

Why fines aren’t enough

The European Commission has made it clear that financial penalties alone will not solve the problem. “The only way to end this conflict of interest effectively is with a structural remedy, such as selling part of the adtech business,” said Commissioner Teresa Ribera.

Thomas Höppner, a partner at law firm Geradin Partners, representing several media and tech associations as complainants in the investigation, highlighted how past experiences show that. He pointed to the Google Shopping case, where the company continued to favour its own specialised services despite prior commitments. He also referenced the Android case, in which the so-called choice screen solution, designed to restore competition, proved ineffective. “The fine made headlines, but the real significance lies in the obligation to resolve a deep conflict of interest,” Mr Höppner said.

You might be interested

As he explains, Google may be required to divest either the services it provides to advertisers, the “buy-side”, or the services it provides to publishers, the “sell-side.” On the sell-side, this would include Google Ad Manager, DoubleClick, and AdX. On the buy-side, it would include Google’s programmatic ad buying tools (DV360 and the display portion of Google Ads), along with the infrastructure necessary for these systems to operate independently. Divesting either side would prevent Google from acting as both bidder and auctioneer in ad auctions, the core conflict.

The only way to end this conflict of interest effectively is with a structural remedy, such as selling part of the adtech business. — Commissioner Teresa Ribera

The potential impact of such a remedy is substantial. According to Ms Cori Crider, a structural remedy could open up a €118bn market. The company now has 60 days to present a concrete plan to end self-preferencing. If regulators are not satisfied, a structural divestment could be imposed.

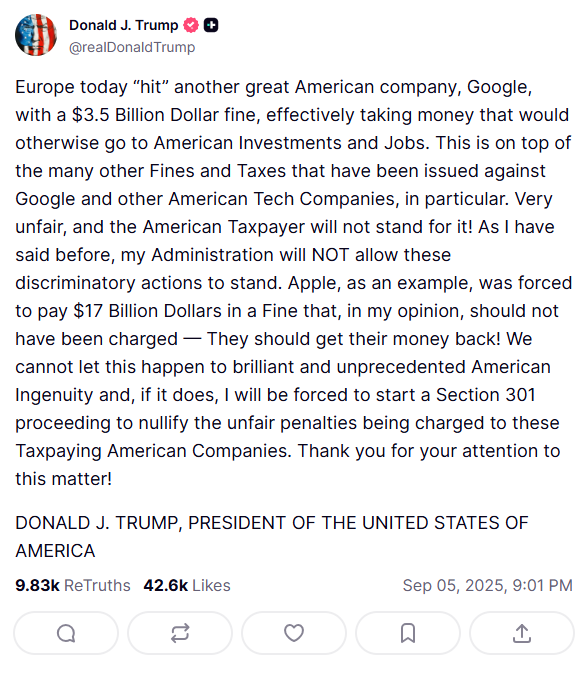

Pushback from Washington

As expected, the ruling has sparked political controversy. US President Donald Trump criticised the fine in two Truth Social posts, claiming the decision was unfair to American business. For him, Europe is “taking money that would otherwise go to American investments and jobs”. Mr Trump threatens retaliatory trade measures.

For Mr Höppner, the Trump administration had exerted pressure on the European Commission to reduce or postpone the fine. Rumours circulated that the Commission considered lowering the penalty below that of a previous €1.2bn AdSense fine or delaying its announcement entirely.

“Ever since Trump came into power, the European Commission had halted the investigation with a view to pending trade talks and Trump’s attempt to portray competition law fines as a form of tariff,” Mr Höppner said.

Yet polling suggests Europeans overwhelmingly support the Commission’s actions. “Two-thirds of citizens want the Commission to enforce its laws, even if it strains relations with Washington,” Ms Crider said.

A lifeline for newsrooms

Beyond tech markets and political disputes, the ruling has profound implications for journalism. By draining advertising revenues from publishers, Google has contributed to financial pressure on newspapers. “Just last year, over 30 European publishers—including Axel Springer and Schibsted—sued Google for more than €2bn, arguing its stranglehold on adtech siphoned revenues away from their newsrooms,” Ms Crider said.

Structural remedies in adtech could allow publishers to retain more revenue, advertisers to secure better pricing, and local newsrooms to survive. “This case is about more than competition law – it’s about whether Europe will still enjoy diverse, independent journalism to inform its citizens,” she added.

The Google adtech case signals a strategic shift in EU enforcement, as behavioural remedies have repeatedly failed. This ruling demonstrates that structural interventions, forcing divestment to remove conflicts of interest, may be the path to restoring competition in critical digital markets.