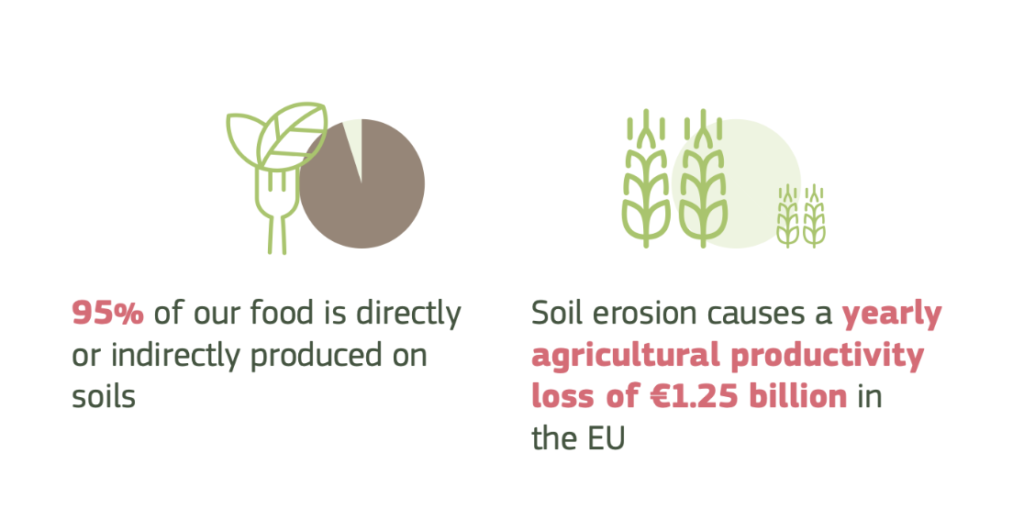

Soil and its quality underpin up to 95 per cent of all food consumed, but at the same time the Earth’s uppermost crust harbours over a quarter of the world’s biodiversity. It is also the largest terrestrial carbon sink on the planet. However, agricultural land in Europe has been declining in recent decades due to industrial activity or urbanisation.

Since 2005, the total area available for agriculture in the European Union has remained stable and is no longer shrinking dramatically, but the way it is used is changing—traditional crops are giving way to new and more profitable ones, for example. The result, among other things, is deteriorating soil quality. Degraded soil contributes to climate and biodiversity problems and limits vital ecosystems. According to the European Commission, this costs the EU at least €50 billion annually.

Official data from the commission shows that, across the EU, 60 to 70 per cent of this exhaustible natural resource is in poor condition. This is set to change, with the Union’s ambition to achieve completely healthy soil by 2050, at the same time as carbon neutrality.

Monitoring every five years

The path to this goal has been set by the fresh agreement on a directive establishing a framework for soil monitoring to enhance resilience and manage contaminated site risks. The directive will also set principles for the reduction of land take resulting in soil sealing and removal. This was agreed by representatives of the European Parliament and the Council of the EU.

In addition to the 25-year horizon for soil “recovery,” the directive introduces new obligations for member states. These include monitoring—mandatory for all EU countries—every five years, and establishing a public register of potentially contaminated soils across the EU. The new regulation should also create a more uniform and coordinated framework for monitoring soil health across the bloc. Last but not least, the directive aims to advance the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda, according to the European Parliament and Council.

“The agreement has enabled us to create the first ever EU-wide framework for soil assessment and monitoring. It is high time to act, as more than 60 per cent of Europe’s soil is not in a healthy state and the situation is deteriorating further. Healthy and resilient soil is crucial to ensure safe and nutritious food and cleaner water for future generations,” said Paulina Hennig-Kloska, Polish Minister for Climate and Environment.

You might be interested

The European Commission, referencing the 2021 EU Soil Strategy, stated that the main cause of the current alarming soil condition in Europe is the absence of relevant Union-wide legislation. Equivalent protection levels exist in the EU for water, marine environments, and air.

A system based on comparable data

The informal agreement between EU lawmakers and the Council awaits formal approval by both co-legislators. If adopted, it should also provide more support for farmers. No new obligations, however, will be imposed on farmers or foresters.

How will monitoring work in practice? European Commission spokesperson Peristera Dimopoulou clarified in a press release that member states would first monitor the health of all soils in their territories and then evaluate them. “This will enable authorities across the EU to provide appropriate support to prevent and combat soil degradation,” she stated.

The Council and Parliament, Ms Dimopoulou stressed, agreed that the new monitoring framework must rely on comparable data from member states. Using a common EU methodology, states will determine soil sampling sites.

“Member states will be required to monitor and assess soil health using common indicators—i.e., physical, chemical, and biological characteristics for each soil type—and follow the EU methodology for selecting sampling sites. To simplify, states may build on existing national programmes or equivalent methods,” said Thomas Haahr, European Parliament spokesman.

The Commission is ready to provide targeted financial and technical support in this respect, he said. “Given varying degradation levels and local conditions, member states will set non-binding sustainability targets for soil health indicators aligned with the overall objective of soil improvement,” Mr Haahr noted.

He emphasised that the agreement imposes no new obligations on landowners or managers. “Instead, it requires member states to assist them in improving soil health and resilience—its ability to perform key ecosystem functions,” Mr Haahr stressed.

Support, he said, can include independent consulting, courses, capacity building, support for research and innovation, or raising awareness of the benefits of healthy soil. Member states will have to regularly evaluate financial costs arising for farmers and foresters from soil quality improvements.

No more land take

The publicly accessible list of potentially contaminated sites must be completed within ten years of the directive’s entry into force. The legislation will also require states to proactively address any unacceptable risks to human health and the environment.

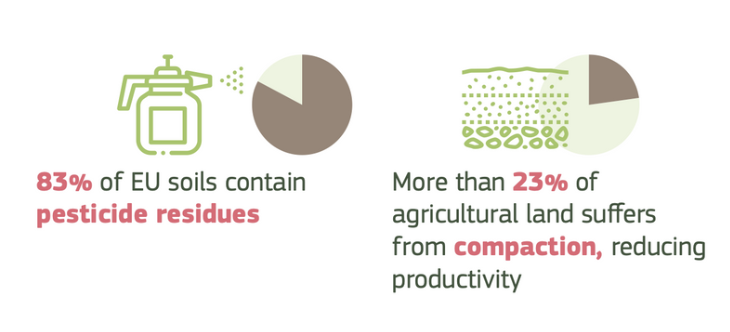

Within 18 months of the law taking effect, an indicative list of newly emerging substances posing serious risks to soil, human health, or the environment must be developed. This is to include, inter alia, PFAS (i.e., “forever chemicals”) and pesticides.

“Today’s agreement is an important milestone in improving support for farmers and all those striving to keep soil healthy. Providing better information and assistance without creating new red tape is the cornerstone of the new soil monitoring legislation,” said Slovak MEP Martin Hojsík, the bill’s rapporteur from the liberal Renew group.

The new directive will, among other things, set out principles for the reduction of land take, focusing on its most visible aspects: soil sealing and removal. “Member states will take these principles into account, while at the same time ensuring that national land-use planning decisions are duly respected. This includes housing, mineral extraction, sustainable agriculture and energy transition,” Ms Dimopoulou, the Commission spokeswoman, added.

The directive also introduces soil health classification based on target and so-called trigger values. The non-binding EU-wide targets reflect long-term goals, while the trigger values—set at the sole discretion of member states—activate specific measures to prioritise actions for achieving healthy soil.

The Commission takes a tough approach

The directive’s origin dates back to 2021, when the European Parliament’s soil protection resolution urged the Commission to propose an EU-wide legal framework focusing on soil protection, sustainable use, and risk mitigation, all in compliance with the principle of subsidiarity.

Parliament demanded the proposal include a thorough impact assessment of the impact of the deterioration of soil quality, and take into account the costs of individual measures, as well as the so-called zero option—i.e., the costs of inaction—in terms of the environment, human health, the internal market and sustainability.

The Commission submitted its own proposal in July 2023. Alongside mandatory five-year monitoring, it included a unified definition of healthy soil and mandatory sustainable soil management.

Member state obligations were precisely and uniformly outlined. The original proposal required states to remediate damaged areas and imposed strict sanctions for non-compliance.

MEPs blinked

The Parliament took a far more lenient approach.

According to the legislators, member states should have the right to choose the key indicators of soil quality according to their own national conditions. Parliament advocated a far more lenient approach. MEPs argued that member states should be able to select key soil quality indicators based on national conditions. They rejected mandatory sustainable management, proposing a “toolbox” of soil management tools instead, and opposed sanctions for non-compliance.

For soil assessment, legislators proposed a five-tier scale from high quality to critical degradation. The Agriculture Committee initially sought to give states 10 years to upgrade critically degraded soil to “degraded” status and 6 years to improve from “medium” to “good.” However, the Parliament’s plenary session later rejected the mandatory timelines.

The Council pushed through a compromise

The Council of the European Union’s stance last June was something of a compromise. Like the two previously mentioned institutions, it supported the basic objective of having healthy soil no later than by 2050.

The Council retained the ambitious target of zero net land take by 2050 but joined the Parliament in opposing sanctions; it also framed sustainable soil management as guidance rather than obligation. The final form of the directive closely resembles this compromise, according to available information.

It retains the aspirational (if non-binding) 2050 target and the two-tier quality assessment, just as the Council did,reflecting the Council’s emphasis on a common EU monitoring methodology with national flexibility in implementation and sampling site selection.

In addition, the final proposal omits sanctions as advocated by the bloc’s executive, but retains the Commission’s structure for monitoring physical, chemical, and biological parameters.

The directive is now due to be formally adopted by the Council, followed by Parliament’s second-reading approval. The directive enters force 20 days after EU Official Journal publication, with member states having three years for implementation.