Initially oblivious of its own security, the European Union is now growing up. The new identity is increasingly defined by vital defence and security interests, resulting in a growing military use of technology. According to Privacy International, a London-based NGO, this shift is evident not only in policy but in the way the EU embraces technologies used in modern conflicts such as Gaza and Ukraine.

“We’ve observed that many companies we have long tracked for surveillance, policing, or commercial purposes are now operating in conflict zones almost naturally, without anyone asking whether this should raise concerns,” Ilia Siatitsa, programme director and a senior legal officer at Privacy International, told EU Perspectives.

At the same time, the transfer of technology between military and civilian sectors is nothing new. “Many of the tools we use every day—like touchscreens or GPS—originated from military projects,” Ms Siatitsa explains. “Collaboration between the two sectors has always existed.”

Ukraine: Europe’s new testing ground

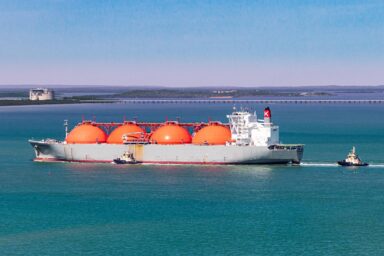

What’s different now, she warns, is the pace and scale of that exchange—especially when it comes to data-driven technologies. “In Ukraine, for instance, the use of technology has been striking: the integration of commercial satellite data with military intelligence enabled preventive action even before the official outbreak of war. Early movements of Russian troops were first spotted by users on TikTok and Twitter.”

Ukraine has become a testing ground for emerging technologies. Companies such as Palantir, which started as military contractors before expanding into health and humanitarian data management, were among the first to offer services to the Ukrainian government. “Clearview AI also pursued contracts there—securing its first deal in Europe. And of course, there are cases like Elon Musk’s Starlink, and others,” Ms Siatitsa adds. Clearview AI’s involvement came despite being sanctioned by at least five European authorities for GDPR violations.

You might be interested

“It’s crucial that wartime or emergency justifications don’t erase existing protections,” Ms Siatitsa says. “AI systems depend on continuous data flows and encourage ever-wider data collection—often far beyond the actual warzones. Just as Israel has used Gaza as a testing ground, Ukraine has become a similar laboratory, with ripple effects across Europe.”

Data as a weapon

Privacy International warns that the concept of what counts as ‘militarily relevant data’ is expanding rapidly. “Today, beyond infrastructure and logistics, civilian data—including information gathered by Facebook and Google—is also being used. All major tech companies have now withdrawn their previous commitments not to share data for military or surveillance purposes. In February 2025, Google was the last to do so,” the NGO notes.

The implications are serious. There have been documented cases of foreign soldiers being identified through commercially sold data. One American company, for example, reportedly purchased datasets containing information about German soldiers from a data broker. “This constant collection of personal data makes us vulnerable—even in times of peace,” Ms Siatitsa says.

We need to ensure that these existing principles guide decisions even in wartime. — Ilia Siatitsa, Privacy International

The NGO warns that limiting the militarisation of technology—even when both the EU and Ukraine agree—is increasingly difficult. “We’re in a global race for technological and data dominance, driven by political narratives. Unfortunately, Europe is entering this race rather blindly, without realising how exposed we are to private companies—Western or otherwise. This race makes us more fragile, not safer.”

Europe’s changing vision

In the past, EU-funded research had to prove it had no military applications. Today, however, many European defence startups—some supported by EU programs like Horizon Europe—are developing technologies specifically designed for military use. Meanwhile, regulations such as the GDPR and the AI Act include broad exemptions for defence and national security, meaning they do not apply in those contexts. Even strategic plans like EU Readiness 2030 (initially known as ReArm Europe) signal a departure from the Union’s founding ideals of peace and cooperation.

“Unfortunately, there are no effective oversight mechanisms to monitor these transformations,” Ms Siatitsa explains. Still, Europe retains a robust international legal framework for data protection and privacy. The problem, she warns, is that military exemptions often undermine its effectiveness. “We need to ensure that these existing principles guide decisions even in wartime. International humanitarian law already contains clear protections that states are obliged to respect—and it’s our duty to remind them of that.”