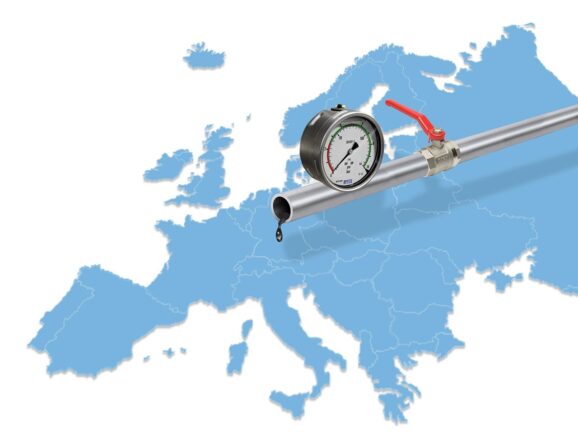

European governments have agreed rules to stop buying any Russian natural gas. Imports will face curbs from 1 January 2026 and a full ban from 1 January 2028. Existing short-term deals may run until mid‑2026 and long‑term contracts until 2028.

The European Council agreed on Monday, 20 October its negotiating position on a draft regulation to phase out imports of Russian natural gas. The regulation sits at the core of the EU’s REPowerEU roadmap. The move aims to cut Moscow’s leverage, force diversification of supplies and speed investment in alternatives such as LNG, renewables and storage.

The proposed regulation introduces a legally binding, stepwise prohibition on both pipeline gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports from Russia. A full ban will apply from 1 January 2028. The Council’s agreement preserves that deadline and signals a willingness to deliver the phase-out.

Although we have worked hard and pushed to get Russian gas and oil out of Europe in recent years, we are not there yet. — Lars Aagaard, Denmark’s energy minister

The Council confirmed that imports of Russian gas will be prohibited from 1 January 2026, while maintaining a transition period for existing contracts. Short-term contracts concluded before 17 June 2025 may continue until 17 June 2026; long-term contracts may run until 1 January 2028. Amendments will be allowed only for narrowly defined operational purposes and cannot raise volumes.

The legal frame

Lars Aagaard, Minister for climate, energy and utilities of Denmark, commented: “An energy independent Europe is a stronger and more secure Europe. Although we have worked hard and pushed to get Russian gas and oil out of Europe in recent years, we are not there yet.”

The regulation also sets customs and authorisation rules to make the ban operational. The Council streamlined customs obligations compared with the Commission’s proposal. It established lighter documentation requirements and procedures for imports of non-Russian gas.

You might be interested

For non-Russian gas authors must see proof at least five days before entry. For Russian gas and imports in the transition phase the information must be submitted at least one month before entry. Mixed LNG cargos must show the respective shares of Russian and non-Russian gas, with only the non-Russian amounts allowed to enter.

How it actually works

The Council requires a prior authorisation regime for both categories of imports to ensure the prohibition works in practice. Member states may exempt imports from countries that meet criteria outlined in the regulation — so not all shipments face the same paperwork. The Commission will draw up the list of exempted countries within five days of the regulation’s entry into force.

To reduce administrative burden the rule excludes some imports from prior authorisation (notably those from countries that satisfy the specified criteria). The approach targets checks where they matter most. Additional monitoring and notification mechanisms aim to prevent Russian gas from entering the EU under transit procedures.

The regulation obliges all member states to submit national diversification plans. These should set out measures and challenges to diversifying gas supplies. States that can demonstrate they no longer receive direct or indirect Russian gas may claim an exemption from that obligation.

Diversification plans

The Council extended the diversification-plan requirement to oil imports where relevant. The aim for oil mirrors the aim for gas: discontinuation by 1 January 2028. The Council also improved information exchange between national authorities, ACER and the Commission. It tasked the Commission with reviewing implementation within two years of entry into force—including the prior authorisation provisions. “It is crucial that the Danish Presidency has secured an overwhelming support from Europe’s energy ministers for the legislation that will definitively ban Russian gas from coming into the EU,“ Mr Aagaard said.

The suspension clause gained clarification. The text specifies the types of disruption to the security of supply that could justify a temporary lifting of the import prohibition or of the prior authorisation requirement. The Council presidency will now begin negotiations with the European Parliament once the latter adopts its position.

The text the Council agreed brings regulatory detail to a political choice. It seeks to deliver a resilient and independent EU energy market while preserving security of supply. It blends short-term transition measures with legal certainty about the end date for Russian imports.

Strategy, motives, trade-offs

The case for the phase-out rests on three broad objectives set out in the agreed material. First, energy security: reliance on a single supplier creates leverage and exposes the Union to infrastructure risks. Second, strategic autonomy: heavy energy ties limited political room for manoeuvre and reduced collective action. Third, economic and market reasons: Russian gas financed part of the Kremlin’s budget and reducing purchases removes that revenue stream.

Environmental policy reinforced the case. Decarbonisation pushes member states toward renewables, efficiency and electrification. Reduced gas demand supports climate targets and lowers long-term exposure to volatile fossil-fuel markets. The Commission and capitals judged transition costs preferable to the strategic risks of continued dependence.

It is crucial that the Danish Presidency has secured an overwhelming support from Europe’s energy ministers for the legislation that will definitively ban Russian gas from coming into the EU. — Lars Aagaard

Practical measures sit alongside the regulation. Emergency diversification, LNG contracts, import terminals and alternate pipeline supplies form the short-term response. Demand reduction, storage fills and coordinated sharing underpin collective resilience. Medium-term investment in renewables, interconnection and hydrogen research aims to replace gas in industry and heating.

Implementation hurdles

The transition carries challenges. Replacing large volumes of pipeline gas needs substantial investment and coordination. LNG terminals and long-distance supplies cost money and take time to scale. Consumers and industry may face higher bills if prices rise during transition. Member states must manage those trade-offs while meeting the regulation’s deadlines.

The Council’s text tries to limit disruption. It keeps narrow flexibilities for landlocked member states affected by changes in supply routes. It allows only operational amendments to contracts and sets clear timelines. The Commission’s two-year review will test whether the prior authorisation regime and monitoring suffice.

The regulation crystallises a deliberate policy choice. It aims to reduce Moscow’s leverage, increase the EU’s freedom of action and accelerate the energy transition. The law ushers in a gradual end to Russian gas—subject to the political negotiations to come.

The Council presidency will now start negotiations with the European Parliament. Once MEPs have adopted their position on the matter, the regulation is likely to pass the entire process in full.